|

By Nadia Dalimonte George MacKay and Léa Seydoux in The Beast The power of what it means to be human is put on ambitious display in Bertrand Bonello’s The Beast, a hypnotizing sci-fi odyssey that spans time and space. Adapted from Henry James’ 1903 short story The Beast in the Jungle, Bonello swirls a techno future with a contemporary Lynchian L.A. noir and an Edwardian era love triangle. At the core of these intertwining worlds is Gabrielle Monnier (played by Léa Seydoux), a woman who lives in perpetual fear that something catastrophic will happen. Gabrielle’s fear dates to 1910, around the Great Flood of Paris, when she was a married pianist in mysterious liaisons with an Englishman named Louis (played by George MacKay). The two characters’ first meeting feels akin to déjà vu. Surely their paths must have crossed elsewhere, whether “elsewhere” is reality as we know it, or another version fueled by subconscious drives. Bonello’s film is concerned with losing the beauty of reality and the varied spectrum of emotions, good or bad, that make us human. The fear of not feeling things, and the manipulation of that fear by artificial intelligence, makes The Beast a startling modern day horror story. In Bonello’s version, the beast is brought out of the jungle and into a bleak dystopian future.

The Beast sets the stage with a futuristic concept that is both technologically advanced in its practices, and hauntingly realistic in its ideology. Partly set in 2044, the story takes place in a society where everyone’s lives are dictated by artificial intelligence, and human emotion is considered dangerous. To achieve neutrality, citizens purify their DNAs by undergoing a “purification” procedure that deletes centuries-old inherited trauma. Past lives are eradicated to cleanse human beings of emotion, so that life can be surface-level and free of complexities. When Gabrielle undergoes the procedure, she is faced with simulations of her past lives, among them an esteemed pianist in 1910 Paris, and a club-hopping house sitter in 2014 Los Angeles. In each decade, she encounters different versions of Louis (MacKay). The film introduces his character at a 1910 high-society party, where he exudes the energy of a tempting and passionate suitor. Yet there is something about his interactions with Gabrielle that carry an aura of impending disaster, as though another version of Louis is lurking in the shadows, ready to pounce. The 2014 storyline drags the most horrific version of him into the light: Louis Lewansky, a 30-year-old virgin of incel ideology who vlogs about how magnificent he is, and that women deserve to be punished for not being with him. Through this despicable character, Gabrielle still senses her past lover buried deep within; for instance, after an earthquake rattles the streets of L.A., she notices him outside her temporary home and invites him inside. The film leaps through time to show how “the beast” takes on many different forms. Bonello first uses a green-screen environment to frame the story. It is unclear whether Seydoux is playing herself, or simply another version of Gabrielle, as she is instructed in a scene to act afraid of something that doesn’t really exist. Her palpable fear in this introductory scene sets the tone for a recurring sense of dread. Whether in the form of a natural disaster (flood; earthquake), a technological disaster (cyberattack), or a man-made hell (Louis Lewansky), fear ravages through The Beast like a plague. On the surface, the film presents as a sci-fi romance about two lovers reconnecting across space and time. Buried in the passion and yearning lies a deeply unshakable horror story about artificial control and existential dread. Continuing a page in the book of many great horror films, Bonello grounds horror in real fears. The film explores the beasts that we cannot see, hiding in plain sight. Much of what Bonello has to say involves the concerning rise of artificial intelligence, particularly the replacing of humans to generate images void of real emotion. The 2044 storyline is populated with dystopian designs and muted expressions. An invisible substance cloaks the air, prompting Gabrielle to wear an enhanced face mask outdoors. The “purification” centre is surrounded by buildings marked with a year – 1972, 1980, 1963 – and each space has a disco with era-themed music. In Bonello’s future, lives of the past are within easy reach. Most of the scenes are visions of Gabrielle’s past that she experiences during the procedure. In reliving these moments, she becomes torn between wanting to continue living out the past and being fearful of spoiling the present. The play on time travel is a fascinating subversion of storylines that often populate the sub-genre. The story moves back in time not to change something from happening, or to analyze the ripple effect of one incident, but to hold onto what it means to be human. The dread that Bonello explores is that of losing emotions, and reaching a point where artificial intelligence causes a new way of life. Gabrielle speaks of such dread when she reveals, “I’m scared of not feeling things.” Whether good, bad, or everything in between, emotions make us feel alive. To love is to feel, and the romance between Gabrielle and Louis goes against all odds to survive a bleak future. Bonello’s vision for The Beast is brought to life by a spectacular Léa Seydoux as Gabrielle Monnier, the film’s protagonist. Seydoux has the complex role of playing different versions of the same character, across various time periods, within an unconventional narrative structure. The story can be muddled and tricky to fully understand, but the majority of The Beast finds a steady anchor in Seydoux. The role plays to her incredible strengths of timelessness and emotional vulnerability. She carries just as much persuasiveness in the 1910s as she does in the 2010s and 2040s. Seydoux also establishes a powerful heart line that connects all these versions, so that they feel part of one entity. Gabrielle’s heartache for humanity is transfixing to watch, as is her chemistry with George MacKay, who plays her lover scattered across time. MacKay is an actor of impressive range, and he flexes his chameleonic muscles as three versions of his character Louis. The 2014 timeline in particular gives MacKay the most material to work with. He delivers a truly unnerving performance as Louis Lewansky that keeps you in a perpetual state of fear, and leaves you with the depressing fact that many versions of this character exist in real life. The Los Angeles narrative in its entirety gives interesting context to the film overall, while also working as an effective horror standalone. The classical music adds to the nightmarish quality. The Beast marks the first soundtrack composed by both Bertrand Bonnello and his daughter Anna. Together they’ve crafted a mix of intense sounds that can shape a sweeping romance one moment and cut the tension of a murderous spree the next. Much of the imagery also lends to the nightmarish feeling of the L.A. narrative. One of the most frightening scenes takes place in a video call exchange between Gabrielle and an online psychic, while a dangerous figure looms around the house. The psychic, who initially appears in the 1910 timeline as a fortune teller, has an extremely Lynchian quality, from her surreal mannerisms to her ominous dialogue. Even in the face of potential danger, her tone is eerily neutral. In a 1910 scene between Gabrielle and Louis, Louis refers to the doll factory that Gabrielle’s husband owns, and questions why all dolls have the same expression. Their faces are neither happy nor sad, just neutral. The subject of neutrality is often explored through the recurring symbol of dolls in The Beast. The 1910s lay the groundwork, followed by a modern talking doll in the 2010s, and a life-size companion doll (played by a tremendous Guslagie Malanda) in the 2040s. Malanda’s character encourages the endless possibilities of artificial intelligence (“I have many options you know, make the most of me”). This companion can be anyone and anything to Gabrielle, but nothing can recreate the real emotions that Gabrielle fears losing. The Beast is full of bold ideas and grand executions. While the story is not the most coherent to follow, the creative vision puts you in a compelling trance nonetheless. Bonello wraps the intense fear of love with an ambitious sci-fi tale of 20th century affairs, contemporary horror, and a future that isn’t so fantastical. The dependency on technology and advancements of artificial intelligence put humanity in an increasingly vulnerable position. But human emotions are impossible to shake. The Beast tells an expansive, daring tale about what it means to really be alive. The Beast arrives in theatres in Toronto and Vancouver on April 19.

0 Comments

By Nadia Dalimonte Kate Winslet in HBO's The Regime The magic formula of pairing Kate Winslet with an HBO series has been tried and true. 2011’s period melodrama Mildred Pierce from visionary director Todd Haynes won 5 Primetime Emmys, including Lead Actress in a Miniseries for Winslet’s starring titular role. A decade later, 2021’s detective mystery Mare of Easttown from creator Brad Ingelsby won 4 Primetime Emmys, among them a Lead Actress win for Winslet’s lovable Mare. Her performance struck an emotional chord and infused you with a sense of wonder as to what became of the small-town detective. The graceful end to her chapter beautifully stuck the landing. While we may never get another season, understandably so given it’s a limited series (a distinction that’s been played around with as of late), this void left behind can be filled by yet another electric pairing.

HBO’s six-part limited series The Regime, from the producers of Succession, pulls compelling satire from a thinly veiled authoritarian regime. Winslet plays Chancellor Elena Vernham, a delusional dictator of a fictitious country in “Central Europe” whose power begins to unravel. Elena’s synthetic-looking palace, complete with leopard print accents and an underground disco, has become a bubble of her own creation. The clinical palace walls have housed everything from her hypochondria and paranoia to bizarre social media livestreams and meetings broadcasted live from her bathtub. After some time in this absurdist loop, Elena finds a fix for her boredom: Herbert Zubak (Matthias Schoenaerts), a disgraced corporal and assassin who becomes her confidant, and maybe more. With Zubak by her side, the Chancellor finds new ways of exercising her power within the palace and carefully maintaining her image to the country’s people, who she collectively refers to as “my loves.” But her obliviousness to what real people need, and the human rights issues they face daily, is alarmingly dire. Zubak’s growing impact on the Chancellor walks a fascinating tightrope between appeasing to an out-of-touch figure of authority and undermining it for the good of the country. Her grounds for decision-making operate on fear, and a deeply embedded trauma that the series dodges. Elena is a character who always thrives from power, which allows for Zubak’s volatile commands on her behalf to be tuned up at maximum volume. Their dynamic moves to the rhythm of an old rollercoaster where every wobble and creak can be heard. Watching them both navigate a power struggle within their own relationship is dynamite. As executive producer and lead performer, Winslet excels at capturing the darkly comic tone that runs through the veins of The Regime. The world is not ready for how much fun she has bringing Elena Vernham to absurdist life. This character gives one of the most accomplished and versatile actors, decades into her career, a playground to flex brand new muscles. Following up the protective hardshell of a tragically real Mare Sheehan, with a woman so far removed from any semblance of real life, is a thrilling testament to Winslet’s talent. Her sense of humor is also on full display; Elena is far and away the funniest role and performance of her career. From punchy one-liners and singing deliberately out-of-tune, to an entertaining display of physical comedy. The supporting cast rounding out The Regime include Matthias Schoenaerts, brilliantly cast in the role of Zubak. Not only does he balance the intensity of this character’s physicality and stamina, but also the emotional needs that anchor his decision-making. Zubak is hardwired to equate love with pain, which influences his relationship to the Chancellor. While the writing does not flesh him out enough as Elena, leaving more to be desired, Schoenaerts brings a compelling presence to the screen and shares both frightening and amusing chemistry with Winslet. Zubak takes up most of the space around Elena, as her husband (an endearing Guillaume Gallienne) watches on. Other characters operate much like Elena’s husband, mere observers to the madness. Andrea Riseborough, while great as usual, unfortunately does not get as much material to work with as hoped for. The same can be said for Martha Plimpton and Hugh Grant, electric in their roles but missing the opportunity to pack a bigger punch. The Chancellor is the primary source of entertainment in The Regime, and the writers know it. The screenplay smartly focuses on Elena’s character development with an understanding of her performative nature and the sublime talent that Winslet brings to the table. The character’s grip on power is tumbling down in real time, and yet she puts on a bubbly face without a care in the world. Her surrounding government officials propose a ration program to combat the threat of starvation, to which a bored and frustrated Elena responds, “This is Central Europe, no one is starving!” Horrors are unfolding before her very eyes, but her obliviousness knows no limits. The series somehow finds a steady-enough balance between enjoyable and nightmarish. For every biting line, lies a sinister undertone that only grows more powerful. It’s a surreal experience, and the absurdity can be felt from all angles. Whether it’s the exaggerated production design and vague accent work, or the horror-fueled score and the caricature-like people who populate the palace. Most of all, the absurdism radiates from Winslet’s performance, an insanely funny combination of cruelty and pleasure. The Regime airs Sunday March 3 on HBO. By Nadia Dalimonte Daisy Ridley in Sometimes I Think About Dying Sometimes Fran likes to think about dying. Not necessarily because she wants to, but out of morbid curiosity. How would it feel to hang off a crane? To drink poison? To lay alone in a forest, so far removed from the physical world? Thoughts of death occupy the frontlines of Fran’s mind as she goes about her work day at a drab office in coastal Oregon. While co-workers give weight to water cooler conversations, she awkwardly keeps to herself and watches in silence on the sidelines. But all that changes when she meets Robert, the new employee with whom she feels an indescribable spark. As their conversations evolve from spreadsheets and emails to movies and relationships, Fran faces the ultimate test: will she feel comfortable enough to let Robert in to her otherwise solitary life? Director Rachel Lambert finds a confident rhythm with Sometimes I Think About Dying, a compelling gem in the “less-is-more” corner of storytelling.

Carrying the film with striking impact is an incredibly restrained Daisy Ridley. With every little glance, she lets the viewer pick up on her character’s hesitance of those around her. She might be seen as invisible by her co-workers, but her personality stands out in the moments of awkward silences. During a meeting where colleagues are asked to introduce themselves followed by their favorite cheeses, Fran matter-of-factly states that she likes cottage cheese. In the stillness that washes over the room, she catches the attention of Robert (Dave Merheje), unbeknownst to her. The two strike up a virtual office chat afterwards, and a new layer of Fran is explored. Ridley’s performance acts as a gentle guide through this character breaking out of her shell with the hope that she will be understood. Crucial to the film’s staying power, Fran’s introversion is explored from a perspective that recognizes how much she tries to interact in social situations. She listens intently to the conversations happening around her, as though deciding at what point she ought to join in. While sticking to the wallpaper of a social interaction, she still lets her presence be known, even if her colleagues refuse to acknowledge it. With the introduction of Robert into her life, she opens up in ways that one would not expect and delights in the opportunity to be known by someone else. The story’s mundane office setting adds another layer to how impactful her delight is. Robert’s presence lights up an otherwise draining, monotonous environment for her. It’s in the moments left unsaid between them that she develops a connection, and in their voiced one-on-one conversations that she finds a way to let her guard down. The journey to that point is not an easy one for a character of Fran’s sensibility, which the film depicts with striking relatable qualities. Fran and Robert’s relationship evolves in a refreshingly honest way that puts weight on both of their roles; her attempts at letting him get to know her, and his embrace of the time it will take to reach that level of understanding. Sharing the screen with Ridley, Dave Merhe brings exceeding warmth and charisma to his character. From his passion for movies to the way he lovingly teases Fran, Robert is an endearing personality whose directness and honesty help give Fran some clarity about what she wants. Their melancholic final interaction in the film would not hit as hard emotionally without Merhe’s understanding of how Robert’s presence makes Fran feel. As well, the chemistry between Ridley and Merhe accentuates the initial butterflies that swell on first dates and the early process of getting to know someone. Whether Fran can trust Robert with opening up, sharing her fears and desires, gives the film a strong narrative focus. In addition to Ridley and Merhe’s performances, an unsung standout of the cast is Marcia DeBonis as Carol, the employee who has reached her last day at the office. DeBonis, one of the most prolific character actors in the industry, brings an immediate warmth to the film. Her naturalistic work builds to a compelling moment between Marcia and Fran in the final act, which calls out a depressing reality. For all the work people put into their jobs, they can miss out on life, and most of all the loved ones they choose to spend it with. DeBonis’s understated work speaks to the very human need to be included. Whether it's an office setting where one can present the most conversational version of themselves, or a personal vacation where one can release from mundanity. While the pacing of Sometimes I Think About Dying add to the dreary atmosphere, it also maintains a sense of repetitiveness to a slight fault. It may not come as a surprise that the film is based on a short of the same title, written and directed by Stefanie Abel Horowitz. Stretched into feature length, the nuances of Fran’s introverted experience navigating love and work feel too drawn out for the purpose of filling in space. One too many scenes of Fran zoning out at the office make the film feel overlong in its runtime. Once the relationship between Fran and Robert kicks in, the story takes on a more dynamic shape. Helping to break up the office mundanity is the film’s use of imagery and sound. Whether a long take focused on a crane, or a shot of a “deceased” Fran laying in the forest, the visuals are a vivid reflection of her mind. As well, the use of music conveys the feeling of watching a fairytale and constantly hoping the best for Fran. Dabney Morris’s original score has the sounds of a sweeping romance. Adding to the fairytale is the choice of including a poignant tune from 1937’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. “With a Smile and a Song” arrives at a point in the Disney film when Snow White reassures the forest animals not to worry, she won’t leave them. She asks the birds what they do when things go wrong, and the birds sing a song. The use of this Disney tune in Sometimes I Think About Dying not only builds on the film’s recurring forest imagery, but also adds a thought-provoking layer to where the story leaves Fran. Her realization that Robert doesn’t know her at all, and her willingness to change that, is a sweet embrace of someone working their way through loneliness. Sometimes less is more, and in focusing on Fran and Robert’s serene embrace, as forestry surrounds them, Rachel Lambert creates a rich vision of the central character’s growth. She finds a way to let Robert in. By Nadia Dalimonte Camilla Morrone and Joe Keery in Marmalade The heist romance sub-genre is given a peculiar spin in Keir O’Donnell’s directorial feature debut Marmalade. The film wastes no time getting right to the story of Baron (Joe Keery) and Marmalade (Camila Morrone), an ill-fated couple caught in a whirlwind of robbery. But the couple’s relationship manifests out of thin air, as do their individual motives and what drives them towards each other. Character development gets lost in the whiplash of hasty editing and questionable narrative choices, all of which the mostly reliable cast can’t quite rise above. From the underdeveloped central romance and subplots, to the uneven pacing, Marmalade doesn’t reach that sweet spot of balancing what makes both the romance and the crime compelling.

Marmalade starts with a recently imprisoned Baron and his newfound friend, cellmate Otis (Aldis Hodge). What starts as a cryptic chat turns potentially fortuitous for both of them. Baron has a secret stash of money hidden outside the prison walls. If Otis can help him escape, that money will be free for the taking. To explain how and why this money exists, Baron turns back time to explain how he met Marmalade (Camila Morrone). The two quickly fall in love and plan a Bonnie and Clyde-style bank robbery to kickstart a new dream life together. In the midst of scheming, Baron also cares for his sick mother, whose identity remains a mystery throughout the story. There is more to Marmalade than meets the eye, but the reveals add more confusion than enlightenment on what the intention is. The performances, while mostly committed to O’Donnell’s storytelling, offer no real insight into who these characters are beyond their actions. Joe Keery of Stranger Things fame has an expectedly charming screen presence as Baron. He gives weight to the character’s dumbfounded, seemingly clueless qualities. Keery also manages to balance the film’s odd tonal shifts that take the character on an unexpected journey. The choices O’Donnell makes to reach those unexpected moments, however, make the entire journey feel convoluted. Baron lacks the reliability and strength to be the anchor of this story. From his rushed character development, to underwritten relationships between those in his orbit. Sharing the name of the title, Camila Morrone’s Marmalade is one of the more peculiar elements of the film. Her colorful introductory scene is full of promise and injects a mysterious energy into the story. She appears out of thin air, to the extent that one might question whether or not she is a manifestation of Baron’s imagination. Marmalade is a picture of danger to him. The two’s budding relationship presents the opportunity to embark on an adventure so far removed from his mundane existence. What each character aims to get out of the opportunity poses more questions than answers. Morrone has shown promising talent so far, from playing the lead role in Annabelle Attanasio’s Mickey and the Bear to giving a standout Emmy-nominated performance in the series Daisy Jones & The Six. On paper, Marmalade is another role for Morrone to challenge her range and find a groove in her acting style. While she brings plenty of energy to the role, her efforts feel misplaced and underutilized. As a result, her character’s presence becomes exaggerated and doesn’t quite hit the mark of intended eccentricity. Morrone fares better in the quieter, more dramatic moments where one can sense insight into her character’s backstory. But that aspect of her unfortunately gets sidelined by the film’s uneven focus. To the same degree, Aldis Hodge tries his best with the material given, but his character Otis also feels underutilized. The film sets up a key connection between him and Baron as cellmates, but that connection quickly becomes a device to move the plot around, and neglects to give Otis a sense of his own purpose. The story of Marmalade jumps from Bonnie and Clyde-style passionate crime, to an undercover prison break, to a complete one-eighty jump in a certain character’s identity, lacking the coherence to hold it all together. The film thrusts the viewer into the narrative without establishing a strong enough sense of place, nor getting to know the characters beyond archetypes. The end result is a mishmash of defining features one would find from a lot of crime-romance films, and not a whole lot of singular vision in the writing or direction. Jodie Comer in "The End We Start From" “The End We Start From” begins with a calm before the storm. A young woman (played by Jodie Comer) gazes at her pregnant belly, her eyes filled with wonder. Moments later, water seeps through the door of her London flat. Without a moment’s notice, the entire city becomes submerged by flooding. In the midst of environmental disaster, the woman makes it to the hospital and gives birth to her first child. The end of one world gives way to the start of another: the novelty of motherhood. When the woman, her partner (played by Joel Fry), and their newborn are forced to leave London in search of a safer place, they are exposed to the elements of terror and uncertainty. Making her feature directorial debut, Mahalia Belo finds a sensitive balance between moments of calm and panic. Despite some uneven pacing and undeveloped plot points, a remarkable Jodie Comer makes the film resonate as a poetic and muted character study. Grounded by Comer’s work, “The End We Start From” is a gentle post-apocalyptic drama that branches into an intimate depiction of motherhood and existential crisis.

Based on Megan Hunter’s 2017 debut novel of the same name, “The End We Start From” is far more hopeful than many dystopian-set stories tend to be. From the protagonist (Comer)’s befriending nature towards her surroundings, to the uplifting visions she has of her partner when the fate of his character is unknown during the film’s second act. The story has a fragmented structure that effectively frames what the protagonist is going through. As her mind falls to pieces, she holds onto her sense of determination and persistency. She creates a protective bubble around her child, ready to fight for him at a moment’s notice, while also feeling the urge to flee. The film captures these internal perspectives on a strong visual level, from Belo’s observational direction and Suzie Lavelle’s cinematography, to Arttu Salmi’s fluid editing. There is a lulling quality in how one scene flows to the next, with occasional breaks of intensity during moments of impending danger. The delicately filmed opening sequence is a fine example, paralleling intense images of the birth and the flood without becoming too on-the-nose in its metaphorical comparisons. Weathering the storm of “The End We Start From” is a magnificent Jodie Comer, who delivers some of her most contemplative and layered work yet. Her character’s frame of mind acts as a guide for direction, and in the hands of Comer’s talent, the story finds its footing. Comer brings exceptional attentiveness to a new mother’s physical and psychological journey, while also attuned to the environmental changes that push her into isolation. Her presence alone establishes a magnetic connection to the viewer. Comer is the anchor to the film’s non-linear storytelling. From her sense of humor and impromptu expressions of joy, to moments of deep existential crisis where she questions her place in the world, Comer finds the layers to this role. Her processing of extreme change makes for complex material to watch. Over the past 8 years, screenwriter Alice Birch has covered an exciting breadth of material; from 2016’s “Lady Macbeth” (Birch’s film debut) and 2020’s Emmy-nominated “Normal People,” to 2022’s “The Wonder” and this year’s Emmy-nominated “Dead Ringers.” Birch’s adaptation of “The End We Start From” continues in the vein of character-driven stories that speak to women’s experiences amid some sort of collapse, whether societal or internal. Her dystopian screenplay tackles a bit of both – the breakdown of London’s infrastructure, and the disintegration of individual life within it. Comer’s character not only has to face survival on a practical level, but also question where she fits in a new world. Plus, layered within is her constantly evolving journey of motherhood. While the themes are well balanced, the story sometimes moves at an uneven pace and engages in unfocused plot points. Outside of the protagonist’s perspective, the film jumps too far ahead with its introduction of vague supporting characters. When the family finds temporary solitude with her partner’s parents (played by Mark Strong and Nina Sosanya) at their countryside home, the writing of those new characters feels too abrupt to make an impact. Strong and Sosanya are given very little to work with. Faring a bit better is Katherine Waterston’s character O, a mother also in search for safety and whom the protagonist meets at a commune. Waterston brings refreshing spark and charm to the screen, making her role memorable. She and Comer share intuitive chemistry that speaks to their characters’ intense, empathetic bonding. In one of the most endearing scenes of the film, the two of them walk through dirt roads while scream-singing the lyrics of the classic ballad “I’ve Had the Time of My Life.” The film has a missed opportunity by not exploring their bond in further detail, as the buildup to their final scene doesn’t quite hit the intended emotional mark. The film at its core is about a woman figuring out how to be a mother, and rediscovering her sense of self in the process. Despite the dangers ahead, and the potential benefits of her family splitting up to get help, she firmly argues, “We have a baby, we’re a family…we stay together.” Despite clear roadblocks and words of discouragement from others in her path, she desperately tries returning back to London, even if it means giving up safety elsewhere. London is home; without that sense of place and stability in her mind, she feels lost. This is beautifully conveyed in the film’s final act, when she questions to herself, “Where am I?”. Comer’s utter helplessness and disorientation in that moment are stunning to watch. Moments like this speak to the strength of her commitment and the emotional resonance of Birch’s screenplay. Beyond the acting and writing, the production of “The End We Start From” also calls attention to the tone that Belo’s direction goes for. The various sounds of water are captured effectively throughout the film, from intense moments of flooding to raindrops falling onto windows. The sound design builds tension and creates a palpable atmosphere around the characters. The film utilizes a limited budget to impressive results; the special effects have an organic and realistic quality to them, particularly when it comes to rooms being submerged in water. The score by Anna Meredith also stands out; while it does feel out of place in a few scenes, its overall intensity captures the sentiment behind the story. “The End We Start From” may be a little too muted in its approach and uneven in its storytelling, but Comer is such a powerhouse performer that the film simply shines in spite of its flaws. Comer infuses the story with a range of messy human emotions that makes it impossible not to feel connected. Playing a character who tries to find her footing between the impact of crisis and the escape from it, she taps into the film’s resonant themes and guides the viewer on a grounded journey. The power of her work rests most vividly in the moments she leaves unsaid; a single glance can evoke just as much as an emotional speech. Coupled with Belo’s steady direction and an introspective character study, the film finds enough ways to resonate. Nathan Lane, Megan Mullally, Aaron Jackson, and Josh Sharp in "Dicks: The Musical" If you thought you’ve seen every iteration of “The Parent Trap,” the most profane and preposterous version likely to ever exist has arrived. Absurd is the word for “Dicks: The Musical,” an off-the-wall concoction that simply has to be seen to be believed, though not without notice of its acquired taste. Directed by Larry Charles, known to offend with Sacha Baron Cohen-led films such as 2006’s “Borat,” 2009’s “Brüno,” and 2012’s “The Dictator,” the film is an outrageous queer comedy that outdoes its ridiculousness on every turn. Co-writers Aaron Jackson and Josh Sharp engage with a specific tone and take on the switcheroo synopsis of “The Parent Trap” – twins who discover they had been separated at birth switch places to reunite their estranged parents in the hopes of piecing their family back together. Insanity ensues when it turns out the twins’ parents are absolutely bizarre, made especially unhinged by the musical acting stylings of Megan Mullally and Nathan Lane. While not all of “Dicks: The Musical” successfully lands at all, and it can be obnoxious to watch, there is never a dull moment with the swing it takes on a comedic and visceral level.

Based on the off-Broadway show “Fucking Identical Twins” by Josh Sharp and Aaron Jackson, the story is told from the perspective of two self-centered businessmen Craig (Sharp) and Trevor (Jackson). They behave as alpha males on top of the world. Both are the prized pigs of the sales department at a company that makes wheels, gears, and teeny tiny brushes. The film plays into the gag of Craig and Trevor being identical twins who look nothing alike. The two discover their family ties when a company merger forces them to work together. Their corporate-fueled opening number is chalk full of sharp line deliveries, as well as visual humor such as parody film posters plastered on walls (from “My Queer Lady” to “The Gay Odd Couple”). The number immediately sets the film’s parodic tone, as does the opening text beforehand, which makes a joke about gay actors being “brave” enough to play heterosexual characters. Sharp and Jackson establish a strong satirical lens and self-awareness from the very start. “Dicks: The Musical” continues to build on its absurdity until all hell breaks loose – from a flying vagina, to a pair of gremlin-looking “sewer boys,” and that does not even begin to capture the insanity. At times, the film feels like an experiment of how much craziness can be thrown to the wall, and how much of it can stick. But there is an overall sense of control to the chaos. Sharp and Jackson’s screenplay maintains a consistently unusual vision, and the eclectic performances are fully committed to the gags. Without the actors’ idiosyncrasies and impeccable timing, the film would completely fall apart. Starring as the twins, Sharp and Jackson are appropriately exaggerated and bring a reliable energy to the screen. Part of the film’s humor is in watching their confusion and terror towards their parents’ behavior. As the twins’ estranged mom and dad, Evelyn and Harris, both Mullally and Lane channel characters who feel as though they are from an alternate universe. To make the switch with each other, Craig and Trevor put on terrible wigs and commit very little effort to embody the other’s personality. They are too busy simply anticipating the opportunity to spend quality time with the parent they had never met. Craig wishes for a mother to be anything but kooky (Evelyn is Megan Mullally in kooky mode, times infinity). Trevor wants a father to do all the stereotypically boring dad activities with (Harris is Nathan Lane). Mullally and Lane surpass all expectations, doing and saying things one could never imagine from their wildest dreams. Not only are the actors of service to insane dialogue and outrageous scenarios, but they add unique talent and pathos to the depiction of these characters. Mullally, doing the strangest voice work and sporting the quirkiest costume, puts on a singular show full of surprises. Her character Evelyn is a total recluse who converses in the most peculiar of ways. Her musical numbers are amongst the film’s most surreal moments, as are each one of her deliveries, with lines such as “I switched the tea and the sand again.” As well, Mullally’s use of pauses for comedic effect is a humorous standout. Adding to the surrealism is an excellent performance by Lane; his instantly welcoming presence grows anticipation for what his character will do next. Harris has come out as gay and the only companionship he has is a pair of “sewer boys” named Backpack and Whisper (puppets that look like deranged gremlins) he had found while inexplicably riding a boat down a sewer. Lane’s wonderful timing, grand musical numbers, and underlying poignancy cobble together into an unforgettable performance. Among the ensemble standouts Lane and Mullally, the film has a fun cast including a great narrator Bowen Yang as God (literally) and an entertaining Megan Thee Stallion as the twins’ boss Gloria. Stallion, making her feature film debut, has a catchy musical number “Out-Alpha the Alpha” during which she commands the screen. As amusing as “Dicks: The Musical” can be, mainly thanks to the committed performances, the obnoxious and juvenile humor is more often than not exhausting and tedious to watch. The hit-or-miss jokes are patience-testers, and the unhinged “Parent Trap” concept starts to wear thin far earlier than hoped for. Considering the hyperactive energy of the material, Larry Charles’s direction falls surprisingly flat. The musical numbers are a fun exception, with choreography that plays to the actors’ strengths and physicality of their performances. From Lane’s “Gay Old Life” number, to the entire cast’s “All Love Is Love” at the film’s conclusion. But the world-building outside of those sequences lacks creativity. The writing also veers into repetitive territory, which is especially frustrating given the film’s short runtime. “Dicks: The Musical” will not be for everyone, and it does not always work. It is funnier in hindsight when reflecting on the sheer fact that this film managed to get made, and that Nathan Lane feeds deli meat to his “sewer boys” directly from his mouth, just one example of how unhinged the story becomes. Lane endearingly refers to the humiliation he feels during the end-credit bloopers, having a grand time but wondering what he is doing in the film. As the viewer, this sentiment is deeply relatable. The glimpse into the making-of “Dicks: The Musical” may very well be more amusing than the film itself. Chris Evans, Andy Garcia, and Emily Blunt in "Pain Hustlers" As has been proven time and time again, a star-studded cast is not enough to save a film. David Yates’s “Pain Hustlers,” a glitzy ‘rise and fall’ crime drama about pharmaceutical representatives at the center of the opioid crisis, adds to the toppling list of wasted talent. Such actors as Emily Blunt, Chris Evans, Andy Garcia, and Canadian queen Catherine O’Hara have seen far better material than a dully told scheming tale of greed. Based on the Evan Hughes-penned 2022 book “The Hard Sell,” the film tells the story of a gutsy dancer-turned-sales rep whose quick wit gives rise to a failing pharmacy. The greater the company’s successes, the further they fall down the rabbit hole of criminal activity. Misleadingly flashy editing and energetic choices of music are a stark contrast to the uninspired screenplay that lays flat at the core. While “Pain Hustlers” features charismatic work by the always-great Emily Blunt, her admirable commitment becomes lost in generic storytelling. The film struggles to engage with its compelling subject matter beyond a surface level.

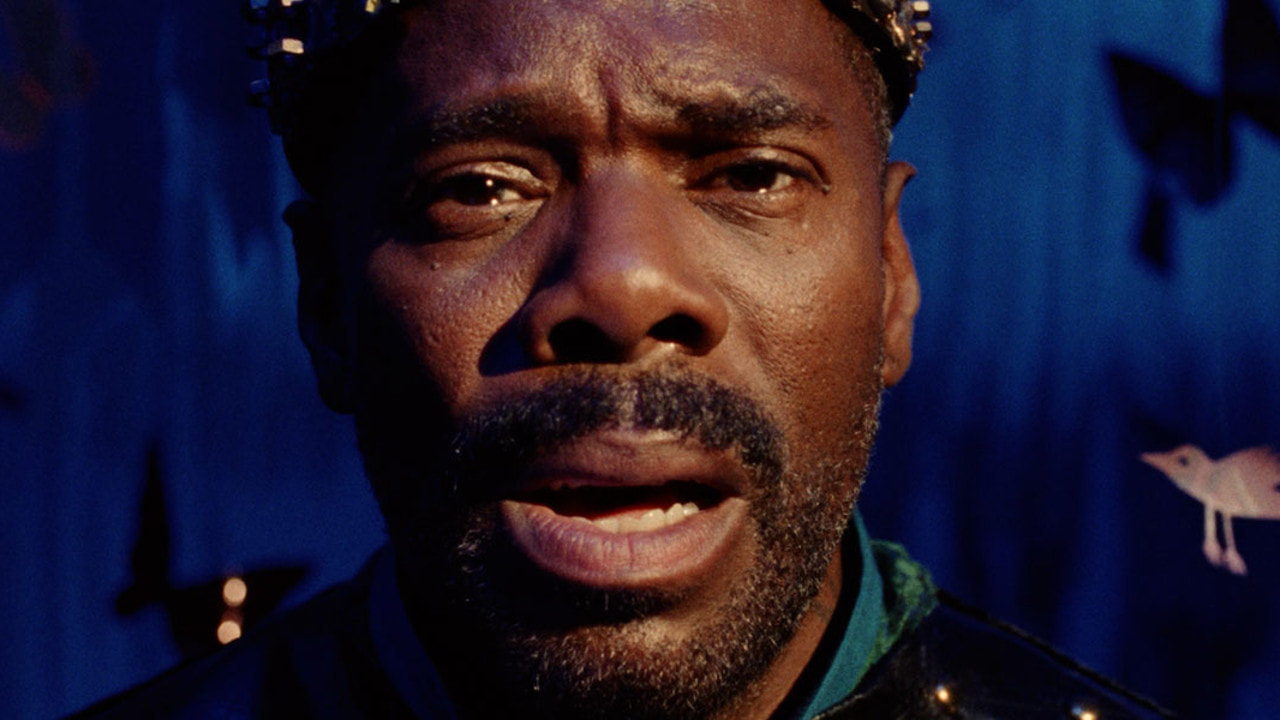

“Pain Hustlers” retells the true story of American pharmaceutical company Insys Therapeutics, which brought the fentanyl product Subsys to market. The company had a direct influence on the U.S. opioid crisis that emerged in the 1990s. In Yates’s glossy film version, the fictional company is called Zanna Therapeutics and it is run by Dr. Jack Neel (Andy Garcia), who pushes the Lonafen (fentanyl) drug initially onto cancer patients as a fast-tracked form of pain relief. Zanna is in need of an economic turnaround. Company executive Pete Brenner (Chris Evans), a gaudy personality in perpetual recruitment mode, visits a strip club in Miami, where he meets the film’s protagonist Liza Drake (Emily Blunt). Liza is a single mother who takes the odd job to make ends meet, and dreams to have a better life for her daughter Phoebe (Chloe Coleman). Working as a dancer at the strip club, Liza receives the so-called opportunity of a lifetime from Pete: a position at Zanna that will skyrocket her bank account. After some thought, she claims Pete’s offer and pleads with him to give her a chance. Pete overhauls her under-qualified resume, and just like that, Zanna has a new cog in its scheming machine. As expected, given the film’s source material, the central conflict of “Pain Hustlers” involves the compromise of morals in exchange for personal and financial gain. Driven by the interests of Zanna, Liza joins in on the Lonafen push. The plan involves visiting various pharmacies and buying off unsuspecting doctors to prescribe the drug to their patients. The targeted patient group begins with people who are undergoing treatments for late-stage cancer. But as Liza’s successful bribing techniques lead to a rapid rise in prescriptions for the company, that target widens dangerously to all patients. The casting of Blunt as Liza is the film’s primary saving grace. She expertly charts the character’s desperation, hunger, and complicity in the grey areas of morality. Though committed as Blunt is, the middling screenplay and generic direction fall short of her talent. The major underbelly of “Pain Hustlers” is corporate desperation and greed at the expense of people’s lives. From the 1990s onwards, the opioid epidemic in the United States has resulted in hundreds of thousands of deaths across the country, not to mention forever-changed families. The over-prescription of opioids and its devastating aftermath has been the subject of many narratives as of late. From the Oscar-nominated documentary “All The Beauty and The Bloodshed,” to the Emmy-winning Hulu series “Dopesick.” “Pain Hustlers” exists in a very different arena in terms of its approach. The screenplay by Wells Tower, based on the Hughes book, lacks the proper nuance to balance an exploration of the opioid subject with the film’s desired comedic tone. In trying to be as pleasing and amusing as possible, “Pain Hustlers” is a dull chore to get on board with until the very end. Not helping matters is Yates’s direction, which breezes through the story and tumbles into the trappings of a glossy ‘rise and fall’ narrative. One particular scene, involving Liza as she appears in a courtroom, arrives at the expected point in the story where accountability takes its toll. However, despite Blunt’s strong screen presence, the scene’s desired emotional impact falls flat. The lack of insightful characterization not only for Liza, but for characters across the board, makes it all the more difficult to feel invested in the story. The cast of “Pain Hustlers” is painfully underused and mostly misguided. Evans and Garcia both veer into one-note territory, though neither make enough impact in the first place to stand out as anything more than serviceable. The saddest of all is Catherine O’Hara’s underused talent. One of the most uniquely gifted comediennes of all time, there was a missed opportunity in utilizing her role to more comedic effect. Reminiscent of the ‘rise and fall’ crime story structure – one that begins on a reckless high until the wrath of consequences catch up – “Pain Hustlers” still manages to lack the entertainment value of a tried-and-true formula. The film also misses an opportunity to explore its characters in further detail, as well as find something recognizably concrete to say in a familiar genre of storytelling. The overall production value may be showy, but the polish quickly fades to reveal a consistently dull experience. While led by a wonderful Emily Blunt, whose charismatic work establishes a connection to the viewer, the screenplay does not reach her (nor her co-stars’) capabilities. Given the scope of the film’s subject matter and the talent involved, “Pain Hustlers” is an unexpected chore. Colman Domingo in "Sing Sing" Since the inception of Rehabilitation Through the Arts (RTA), a theater program that helps prisoners expand their capabilities through creative workshops, the percentage of prisoners re-incarcerated in the U.S. prison system has fallen. Over the course of 25 years, less than 3% of people returned to prison, compared to the 60% national rate. Incarcerated people are given life-changing opportunities to explore their creativity and nourish their vulnerability through the arts. This message of restoration reverberates in each and every frame of “Sing Sing,” a remarkable true story directed and co-written by Greg Kwedar. Based on a real RTA program at Sing Sing Correctional Facility in New York, the docudrama vocalizes an abundance of talent to be found within prison walls. It’s an uplifting experience bursting with heart and soul. It speaks to how theater can heal, and how the power of a safe space can stitch communities together for life. Starring Colman Domingo, Paul Raci, and an ensemble of formerly incarcerated people as well as RTA alumni, “Sing Sing” shines as one of the must-see films of the year.

Behind the walls of Sing Sing Correctional Facility, a group of prisoners sit around a circle deciding on a new play to perform. Their production of Shakespeare’s “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” had gone well, and theater director Brent (Paul Raci) motivates everyone to think of a new story to work with. The group usually looks to mentor and actor Divine G (Colman Domingo) for ideas, and he has one ready to go – a story of overzealous ambition that follows a record player who gets cheated out of his record store. Everyone seems onboard, until the group’s new member Divine Eye (Clarence Maclin) suggests they shake things up and do a comedy. The notion sets Divine G into slight hesitancy. “Dying is easy…comedy is hard,” he poses. But Brent welcomes the change of tone, and soon the entire group brainstorms an eclectic mishmash of ideas – from sprinkles of time travel and Ancient Egypt, to a Hamlet soliloquy and a very amusing Freddy Krueger appearance. Brent cobbles the ideas together into a script called “Breakin’ The Mummy’s Code,” which becomes the troupe’s new production. Inspired by John H. Richardson’s 2005 Esquire article “The Sing Sing Follies,” about a time-traveling comedy (Brent Buell’s “Breakin’ The Mummy’s Code”) that a real group of prisoners performed, the film recounts the play from its inception to opening night. Greg Kwedar’s direction takes a fly-on-the-wall approach to the theater troupe. He immerses the viewer into their environment, giving a front row seat to the inner workings of their energetic stage production. By focusing on what the acting process looks like for the troupe, Kwedar shines a light on how their personal characteristics help inform their sense of playfulness and artistic expression. The viewer gets to know each actor in their creative element and watch them adapt on the fly. The film’s screenplay – co-written by Kwedar, Brent Buell, and Clint Bentley – is structured in a neat way that shows the benefits of the RTA program in action, and lets raw talent soar to exciting places. Between “Rustin,” “The Color Purple,” “Drive-Away Dolls,” and now “Sing Sing,” Colman Domingo is about to have an incredible year in film. The actor’s astounding performance in “Sing Sing” is the finest of his career thus far. Playing Divine G, mentor and organizer of the prison’s theater program, Domingo charts an emotional journey of artistic expression while navigating the realities of the U.S. prison system. As he engages in creative group exercises and aids in putting the production together, he also prepares for his own clemency hearing. The character of Divine G shines further light on how broken and despairing the system is. While pouring his all into theater, preserving the restorative and transformative qualities of the program, the reality of his own experiences sinks in: that in the face of humanity and dignity, lies the inescapability of injustice and stereotype. Domingo’s charming screen presence and insightful character work bring compelling truth to the screen. Among the wonderful cast is Paul Raci, whose fantastic performance in 2020’s “Sound of Metal” has thankfully led to more opportunities such as this one. Raci’s character is based on Brent Bruell, the real theater programming director whose work at Sing Sing has transformed lives. Bringing humanity into a system that is built to destroy it, Raci embodies the character’s intention and spirit. His performance feels so emotionally present, immersed in his surroundings as he shares genuine reactions with the prisoners. The ensemble cast of “Sing Sing” is nearly full of real people playing a version of themselves, from formerly incarcerated actors to various alumni of the RTA program. Their open-hearted performances are an absolute joy to watch. Just seeing them interact, whether during a performance or while expressing a personal moment, gives a candid first-look at how impactful the theater workshop is. It’s incredibly moving to watch the program’s restorative power, plus the creation of a safe space where compassion is shared, people can be vulnerable, and true friendships can form. One of the most resonating dynamics of the film is the bond that deepens between Domingo and Maclin. Their characters initially don’t see eye to eye on a creative level. Divine G has a preference of what material to explore, and Divine Eye’s push for the troupe to do a comedic play presents a challenge. As well, Divine G loses out on the part he wanted to play when Divine Eye goes for Hamlet, ironically the most dramatic role of the entire production. The two characters have a bit of tension, which the film explores in the most organic of ways that simply lets it play out. Through the act of performing together, and in learning about each other’s prison sentences, their deepened bond builds toward a heartfelt final moment. In addition to the cast, the crew of “Sing Sing” reinforce the film’s dynamic energy from a technical standpoint. Pat Scola’s cinematography finds the warmth in moments of reflection and creativity. The detailed production design by Ruta Kiskyte adds to the film’s stage play environment. The editing by Parker Laramie, despite a bit of meandering during the final act, maintains a concise level of pacing overall. As well, the film features a beautiful score composed by Bryce Dessner (of The National). On more than one occasion, Paul Raci’s character Brent goes around the troupe circle and asks everyone to close their eyes. During one instance, he asks the actors to remember a moment that made them happy and let that memory wash over them. In another, he prompts them to think about an old friend and imagine what that person might look like now. The actors’ responses on both occasions, particularly when it comes to happy memories, are key parts of what makes this film so special. The tenderness of “Sing Sing” derives from so many beautiful places, most of all its wonderful ensemble, to which the film sings its tune. From their personalities and idiosyncrasies, inner conflicts and harsh realities, to their hopes and dreams, they define the story. Told with incredible energy and vulnerability, “Sing Sing” is an emotional piece of cinema that challenges a broken system and finds a safe space through the transformative power of art. Kate Winslet in "Lee" The story of Lee Miller is deeply fascinating on paper. From avant-garde muse and fashion model, to war photographer and photojournalist, Miller explored the realms of several worlds in one shot. She went from being the subject of images, to the person behind the lens controlling the perspective. Among her many accomplishments, Miller is responsible for some of the most haunting and piercing images taken from the aftermath of World War II. Miller’s time spent on the frontlines of war, as well as her fight to publish the images she took of the atrocities that happened, are just a snapshot of a trailblazing legacy. To put this role into the hands of Kate Winslet, who plays Miller in Ellen Kuras’s feature narrative directorial debut “Lee,” seems a no-brainer choice. Winslet serves as a producer on the film, her passion project following years of meticulous research and immersion into the subject. Why Lee Miller? The character, entrenched in rich personal and historical material, is an exciting canvas for Winslet to explore. Though while she paints a compelling picture herself, the film leaves more of a blank page behind, leaning too prosaic to fully convey how fascinating a subject Lee Miller is. “Lee” is beholden to Winslet’s emotionally present performance; she brings an energy that the film at times struggles to catch up with.

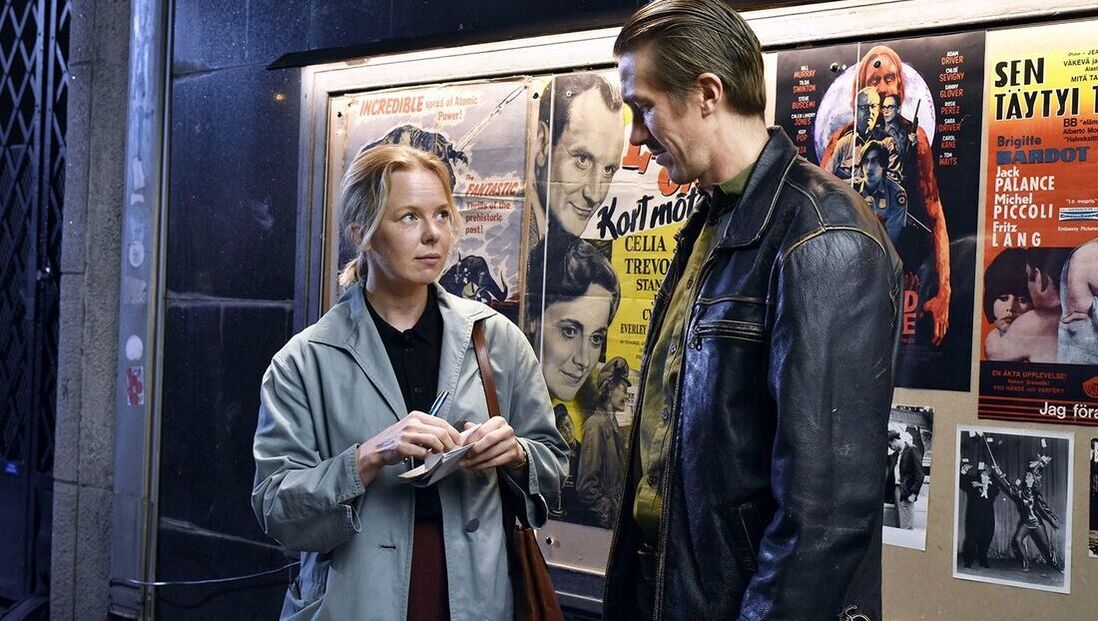

Given the vastness of Miller’s life, it makes sense to focus only on certain periods in a narrative, which “Lee” technically does: frolicking artists in France, London domesticity, and war across Europe. The film begins in the 1970s with an older version of Lee (Winslet) talking to a young journalist Antony (Josh O’Connor) about her life, as they go through a series of photographs in a living room. Winslet narrates the film through time-spanning flashbacks, powerful imagery, and haunting secrets. The story consistently returns to her and O’Connor’s discussion, which reflects on the emotional impact Miller’s photographic work had, not only on her surroundings and the world at large, but on herself. How does she view her past? What personal memory does each image unlock? Director Ellen Kuras explores “Lee” in and around this line of questioning. Nearly everything that the viewer sees is directly through Lee Miller’s lens, with Winslet present in each and every frame. “Lee” tackles the subject’s life from within prominent decades. The first act explores 1930s South of France, where Lee mingles with artistic friends including fashion editor Solange D’Ayen (Marion Cotillard) and artist Nusch Eluard (Noémie Merlant). Lee’s soon-to-be lover, surrealist artist Roland Penrose (Alexander Skarsgård) strolls up to the sun-kissed party, and the two exchange a dynamic conversation, taking turns psychoanalyzing each other. Moments later comes the early blossoming of a romance, and the rest is history. Towards the film’s middle act, Lee moves to London with Roland and becomes his muse. While he paints absurdist works, she finds employment with magazine editor Audrey Withers (Andrea Riseborough) at British Vogue. During her time at the magazine, Lee gets photojournalist accreditation with the American army and joins the front lines of World War II. At this point in the story, she teams up with LIFE magazine photographer David E. Scherman (Andy Samberg) to document the liberation of Paris, the aftermath of Nazi Germany, and the horrors of the concentration camps. All the while, Lee reckons with a painful secret from her past that unravels in the film’s strong final act. Winslet coming to terms with a harrowing experience she had long buried is an astonishing piece of acting. Though the quality of such material is something she doesn’t receive enough of in the film. The screenplay (co-penned by Liz Hannah, Marion Hume, and John Collee) explores Lee’s perspective as a paradoxical figure. On the one hand, she is determined to expose hard-hitting truths. Her voice throughout the film speaks to the urgency of her work and the impact that historical events have on her career (leading to the shift from Miller as a Vogue model to a war correspondent). The realities she witnesses demand to be seen and shared. On the other hand, Lee Miller the person is more of a closed book to some. While she fights to keep photographic memories alive and wants her work to be shared with the world (echoed by Winslet in an impassioned speech to Riseborough), these contributions are kept secret from Lee’s family. The writing explores an interesting dichotomy between which truths to tell, and which to hide. What gives the film intrigue is its questioning of what people ought to (or are ready to) see through Miller’s perspective. Whether it’s the readers of a fashion magazine, those closest to her personal life, or how the subjects of images are portrayed. In a scene between Lee and the journalist Antony, she questions whether he finds it wrong that she posed for a photograph in the bathtub of Hitler’s abandoned Munich apartment. Lee’s question, and the sense of resilience in her demeanor, is a resonating reminder of just how much power an image can hold, decades after being taken. Her determination to capture moments because she feels the significance of them being seen is a sentiment just as prevalent today as it was forty years ago. The screenplay has potential to further explore rich material such as this, however, often goes about telling the story in a surprisingly monotonous way that feels too reserved for its fearless subject. Where the writing lacks in fervor, Kate Winslet makes up for in spades. “Lee” is a wonderful acting showcase for her to live and breathe the character of Lee Miller. Her performance is a fascinating portrait of a no-nonsense spirit who carries the emotional aftermath of repressed pain. She immediately establishes a connection to the audience and gets to the emotional core of Miller. Her exploration of the character’s psyche and fight to tell the truth builds towards a heart-wrenching moment in the final act. In light of her war images not being published in Vogue, she begins to wrestle with a personal truth that comes out. It’s the sort of moment that jolts you to reflect on just how extraordinary an actor she is, which is not a surprise of course, but nevertheless marks exciting new territory in her range. “Lee” is a multi-faceted role that Winslet tackles with remarkable detail and a commanding presence. If only she were given more opportunities within the film to showcase a deeper characterization, as the third act provides. The talented supporting cast of “Lee” is not given much material to work with, beyond moving the plot along. A chameleonic Riseborough stands out as Withers and shares in one of the most heartbreaking scenes of the film. As does Andy Samberg, whose initially aloof presence settles into a subtle and introspective performance. His character Scherman, hyper-aware of his surroundings, eventually reaches an emotional breaking point when he and Lee start visiting the concentration camps and the abandoned Munich apartment. The haunting visitation sequences in the final act are among the film’s most visceral and emotionally charged moments. Kuras shows atrocities through Lee’s photographs, as well as in the reactions on Lee and Scherman’s faces. These sequences highlight the strengths of Kuras’s visual communication with the audience. Alongside the work of cinematographer Pawel Edelman, the decisions on what to show, in addition to when and how, are made carefully. As a photographer and cinematographer herself, Kuras has a unique perspective on visual storytelling. Beautifully exhibited in films such as “Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind” and “David Byrne’s American Utopia,” her cinematography stands out as a vivid reflection of any given environment. She exhibits a similar quality in her direction, bringing a keen eye to the subjects and settings of “Lee.” From intimate close-ups to faraway snapshots, she puts you in Lee’s mindset and sticks as closely as possible to her perspective. The visual focus also rests not so much on Lee herself, but on the artistry created through her photographs. “Lee” follows from behind the camera to capture the character’s initial reactions to images as she witnesses them in real time. The film’s recreations of Miller’s iconic photographs in particular, and the weight they carry, are an impressive feat. While the visual language of “Lee” shines and is anchored by Winslet’s performance, the film is too often weighed down by an inconsistent screenplay and middling pacing. This is especially noticeable considering just how distinctive and accomplished a voice Lee Miller is, not to mention the breadth of interesting material available to cover. Though above all, one of the most resonating takeaways of the film is the discovery of a relatively unknown figure in history, who worked to break through male-dominated spaces and accomplished incredible journalistic milestones. Winslet and Kuras are on the same page in terms of giving their all to bring an extraordinary life to the big screen. While the film does not entirely reach the fascination of its subject, “Lee” is sure to spark greater interest in exploring the legacy Miller leaves behind, and her powerful images that will live on forever. Alma Pöysti and Jussi Vatanen in "Fallen Leaves" The backdrop of Aki Kaurismäki’s tragic romantic comedy “Fallen Leaves” has the makings of a devastating drama. Set in present day Helsinki, Finland, the film tells the story of a sweet romance clouded by a sense of impending dread. Talk of the war in Ukraine fills radio news broadcasts on a daily basis. The film’s protagonist Ansa (Alma Pöysti) listens on in frustration before switching to a more hopeful station, one where wistful love songs crackle through the static. Ansa’s loneliness is as palpable as the setting; the city is painted as a sleepy and almost deserted place. Characters often find themselves at the local karaoke bar or cinema in search of diversion, as though desperately holding onto bits of joy. Writer and director Kaurismäki adopts the same perspective in his storytelling. Amidst a depressing environment of lost souls looking for companionship, he brings levity through sharp dialogue and an amusingly deadpan tone. Every bit funny as it is sad, “Fallen Leaves” finds glimmers of humor and hope in moments of tragedy.

The story begins at a sad-looking supermarket where Ansa stocks shelves on a zero-hour contract. She is eyed intensely by a security officer, who then reports her to a superior for stealing expired food (which would have gone to waste otherwise). Ansa lives a simple, single life. When she’s not standing up against her company’s egregious food waste during scarce times, she spends her days at home listening to the radio, or at the karaoke bar watching life go by. The local bar becomes the setting of a meet-cute as Ansa comes across Holappa (Jussi Vatanen), a lonely trades worker addicted to alcohol. They immediately gravitate towards each other, united by an underlying desire for togetherness and meaningful human interaction. The time that Ansa and Holappa spend together, initially delayed by him losing her phone number and not knowing her name, stresses not only the loneliness within themselves but also the growing necessity of their presence in each other’s lives. Depressing as the story of “Fallen Leaves” can be, the film is a consistently funny and light watch, thanks to Kaurismäki’s poker-faced sense of humor and the equally deadpan performances that compliment his vision. Ansa and Holappa are conveyed in an incredibly ubiquitous way; while the screenplay is specific to their everyday lives, there is something universal about these two characters and their yearning to feel something beyond the confines of mundanity. This universality captures well-rounded characters who can be everything all at once, amusing one moment and miserable the next. In the hands of Kaurismäki, the inscrutable tone of “Fallen Leaves” still manages to be expressive and not alienating. Pöysti and Vatanen each find their way through the characters’ stifled emotions and, in that journey, unveil a resonating wistfulness to them. From Ansa’s depleted facial expressions to Vatanen’s intense blank stares, powerful emotion radiates from the characters. The actors’ chemistry suggests their characters have a mutual understanding of the other’s qualities, almost like an unspoken language that only they can draw from each other. In addition to the performances, the charm of “Fallen Leaves” rests in Kaurismäki’s witty screenplay. The dialogue is brisk and straightforward. Kaurismäki takes a literal approach to the storytelling, which gives the film a down-to-earth quality, especially when it comes to the central romance. Romantic comedies can often exist in a heightened version of reality, where everything seems a little easier and the world feels a little more magical. This of course is part of the charm. “Fallen Leaves” is a pared down rom-com that finds its unique charm in the simplicity and harshness of life. The romance feels naturalistic, and unfolds truthfully with the characters’ personalities as their quiet relationship deepens. Watching Ansa and especially Holappa tame their interior battles to show up for each other on an emotional and physical level gives the film a special staying power. The film’s strength of establishing character extends to the supporting cast as well, particularly Holappa’s drinking buddy Huotari (played by a wonderfully stoic Janne Hyytiäinen). The actor’s presence alone, not to mention his comically recurring one-liners, is a vivid depiction of forlornness mixed with wry self-deprecation. A neat way in which Ansa and Holappa bond is through their appreciation of cinema. The local movie theater becomes a comforting antidote to their cynical world. One of their date nights is a screening of Jim Jarmusch’s “The Dead Don’t Die,” which they both express a liking to. The impact of Jarmusch’s absurdist film extends beyond the two protagonists. It finds its way into a brief conversation shared between two background characters, chatting amongst themselves about how the film reminded them of Jean-Luc Godard’s work. The scene is a fleeting but memorable moment that speaks to how Kaurismäki infuses cinematic influences in a subtle way, whether through pieces of dialogue or through locations. For instance, the local movie theater is used as the setting where Ansa gives Holappa her phone number, and he loses it mere minutes later. There is something incredibly cinematic about him returning to the scene of the romantic crime in the hopes of running into her again. The film works at its best in such moments of quiet, where the camera sits with the characters as they yearn and wonder. The simplicity of Holappa standing by the theater is reminiscent of classic romances that linger in moments of waiting, which can be just as romantic. It may come as a surprise that “Fallen Leaves,” beyond its poignancy and melodrama, is one of the funniest and most optimistic films of the year. The deadpan humor gives weight to the common saying, “If you don’t laugh, you’ll cry.” Kaurismäki adopts this mentality brilliantly, presenting characters in the most unassuming way possible, and then pushing beyond their individual hurdles to reach moments of levity and idealism. While the screenplay becomes too literal for its own good at times, undercutting some of the film’s plot points particularly in the final act, overall it works as a singular expression of Kaurismäki’s distinctive voice in cinema. Bittersweet and endearing, “Fallen Leaves” satisfies in the way a good rom-com does. |

Archives

April 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed