|

Rachel Sennott in I Used to Be Funny From 2020’s TIFF breakout Shiva Baby and 2022’s Gen Z horror Bodies Bodies Bodies, to 2023’s queer high-school comedy Bottoms, Rachel Sennott has made an exciting name for herself on the big screen in just a few short years. Her charisma is a magnet for the camera. Through deadpan observational humor and a grounded persona, she captures deeply relatable social commentary on the millennial experience. In the transition from stand-up comedy to film acting, she has maintained her comedic sensibilities. Though even in humorous roles, whether playing Danielle in Shiva Baby or PJ in Bottoms (a brilliant one-two punch from writer-director Emma Seligman), Sennott shows a terrific knack for the serious bits. She knows when to play a scene for convincing dramatic effect just as well as she can draw dark humor from moments of sadness. Sennott conveys this balance terrifically in writer/director Ally Pankiw’s impressive feature debut, I Used to Be Funny, a smart character study that unpacks trauma through day-to-day female relationships.

The Toronto-based story follows Sam (Sennott), an aspiring stand-up comedian with PTSD who learns that Brooke (Olga Petsa), the teenaged girl she used to nanny, has gone missing. Hearing the news becomes nearly paralyzing for Sam. She ruminates on whether she should join the search, but that would mean leaving her apartment, an act that has become incredibly difficult for her to do. When we first meet Sam, she has trouble eating, sleeping, and socializing. It seems as though performing comedy has been put on the back burner of her life, and the unfolding story reveals why. The dichotomy between Sam’s concern for Brooke’s wellbeing, and own lack of energy towards an attempt to locate her, drives the central conflict of I Used to Be Funny. Pankiw’s sensitive direction and screenplay unearth painful memories from the past that haunt the protagonist’s journey to recovery. The first act mirrors Sam’s frame of mind, and operates in a state of non-linear ambiguity. As she finds herself in the thick of slow progress, faces and objects trigger fleeting memories that pull her back to what feels like another lifetime ago. Sam’s piecing together of the past helps contextualize the present and why her relationship with Brooke is so complicated. Through one of the visual triggers, the film cuts to a few years ago, when the two characters meet at a mansion. Sam is brought in as Brooke’s nanny during an emotional time for the family. Brooke’s mother is ill in the hospital, and father Cameron (Jason Jones) needs help to alleviate responsibilities. Initially, Brooke vehemently opposes the idea of a nanny, but eventually lets her guard down once she and Sam start to form a sisterly bond. But that bond crumbles against the disdain and misogyny of Cameron, who undermines Sam at every point of their communication. His presence carries a terrible uneasiness that takes a turn for the worst. The film takes time to reveal its methods, and sometimes the ambiguity can feel a little out of reach. But once the flashbacks and present-day scenes become more clearly distinguished, Pankiw finds a stronger groove between the narratives. She brings a thoughtful approach to heavy subject matter, and the non-linear structure of her film reflects a very true-to-life movement of healing. The story slowly peels back layers of the protagonist to reveal which truths she has been harboring. This level of storytelling offers a resonating way to build tension around Sam’s perspective. What sets I Used to Be Funny apart from many films that use humor as a framework for tragedy is how both Pankiw and Sennott make this story their own. The writing covers an array of heavy subject matter including sexual assault, trauma, and grief, all explored through the ups and downs of formative female relationships. By focusing on the bond between Sam and Brooke, Pankiw establishes a clear direction of the formative dynamic she wants to capture. Sam becomes a guiding figure for Brooke, and when that sense of guidance becomes lost, the aftermath can be incredibly harmful. The film smartly examines how Sam’s traumatic experience impacts the relationships in her life, from “little sister” Brooke to best friends Paige (Sabrina Jalees) and Philip (Caleb Hearon). In certain scenes, you can feel how Sam’s negative view of herself influences how she believes others ought to treat her. The cycle of trauma and the road to recovery are not a straight line. Pankiw does a beautiful job of showing those ups and downs, and how funny some of those directions can be. In the way that humor can pull you from a hurtful frame of mind in real life, dark comedy carries Sam’s spirit along in the film. I Used to Be Funny conveys a powerful sense of community and togetherness that exists when one have friendships in the comedy world. As well, Pankiw explores the specificity of being a woman in stand-up, which comes with its own set of complications as straight white men have dominated the space far too long. Sennott, having started her career in stand-up comedy, has an acute awareness of this environment. While each show takes tremendous effort and the confidence of putting one’s self out there, Sennott still makes it all look effortless. As well, she adeptly handles the film’s tone and navigates all the subtle changes in her character’s expressions. The film rests on the heights of Sennott’s talent, and her ability to find the humor and poignancy of day-to-day life. Humor is often used as a means of coping. Sam does not see herself as funny anymore; in her mind, how can she be funny after experiencing something so traumatic? The story gently explores how Sam rediscovers her talents and uses that humor to get through a dark point in her life. In addition to Sennott’s performance, the ensemble of I Used to Be Funny combine a great sense of humor with layers of bittersweetness. Casting real comedians Sabrina Jalees and Caleb Hearon) adds a natural energy to the comedy bar scenes, as well as a communal understanding of the emotions Sam goes through of not considering herself suitable for stand-up comedy anymore. As well, Olga Petsa gives a breakthrough dramatic performance as the missing teen girl Brooke. Her character navigates a raw space in which her mother is ill, and she finds a new sense of female guidance in Sam. When their sisterhood becomes compromised, you can feel the heartache of her loss so deeply. Petsa's chemistry with Sennott adds endearing layers to their characters' dynamic. Using humor as a framework, Pankiw tells a poignant story of reconciliation and how relationships can either pull you through or fall apart. While the editing and pacing can be a little too ambiguous, the performances and core themes of the story are unwavering. I Used to Be Funny shows the promise and confidence of a thoughtful feature debut with plenty to say.

0 Comments

A still from Gasoline Rainbow (2024) One of MUBI’s latest and greatest releases now streaming on the platform is the Ross Brothers’s Gasoline Rainbow, a spirited contemporary portrait of young adults. The film follows teenagers from a small town who go on one last adventure before “having to be someone” in the real world. Directed and written with a refreshing openness, the story embraces Gen Z characters who are on the cusp of facing societal pressures. From restlessness and independence, to exuberance and isolation, each character conveys many of the attitudes that come naturally from teenaged perspectives. They have a wide-eyed energy to explore the world beyond what rural Oregon has to offer. As one of the characters muses, “When there’s nothing to do, you just venture. You’re always trying to find something.” The film captures that spirit of roaming through life at its most present, breathing in the natural elements around us that many take for granted. Gasoline Rainbow embarks on the open road with a raw coming-of-age journey into the Gen Z wild.

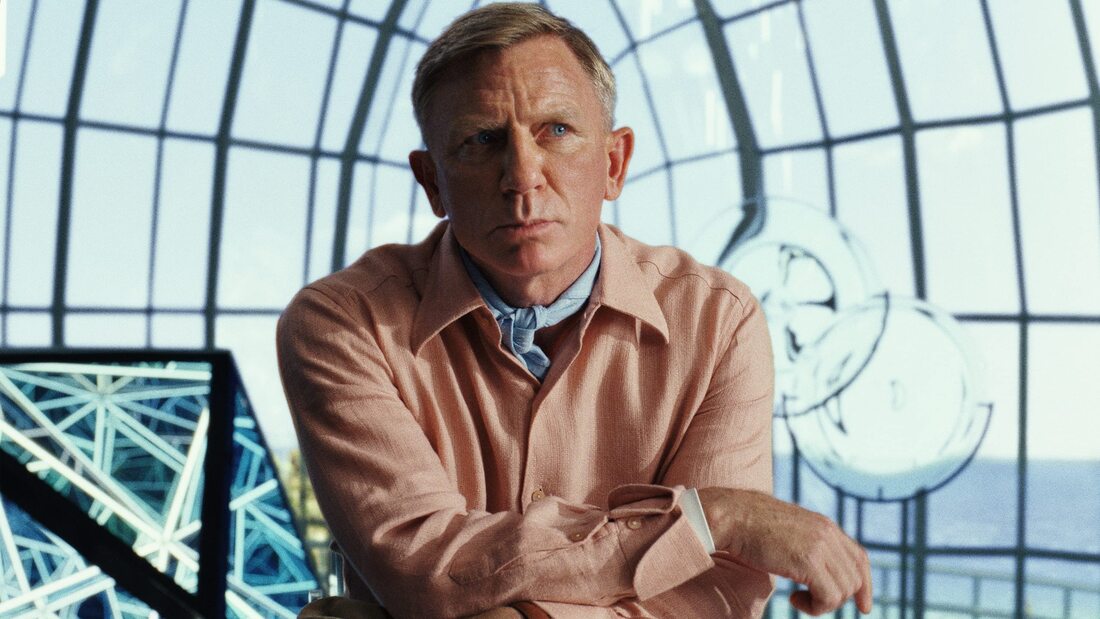

Set in Wiley, Oregon, five teenagers crowd into a van en route to a location over five hundred miles away: the Pacific coast. The purpose of their trip is to enjoy purely uninhibited quality time together. They traverse through the American west seemingly without a care in the world, but as the film’s narration unfolds, they each harbor some level of burden about their experiences thus far and what the future will hold. The film navigates in a space where home is everywhere but also nowhere, which realistically encapsulates the young adult experience. With adulthood in the rearview, the world is their oyster, filled with pearls of possibilities. The story moves at a leisurely pace to capture how responsibilities feel miles away. The lack of narrative structure also strips the film of typical coming-of-age plot points, allowing feelings and vibes to paint a picture. Self-exploration takes a front seat and drives where the story is headed. Gasoline Rainbow has a roaming, up-close and personal direction that meets characters without judgment or predisposition. Much of this film operates on the energy that the cast bring to their roles. The performances feel so naturalistic and mirroring that it’s a wonder whether the actors are playing themselves or totally adopting a character. Blurred lines between reality and fiction give the film a documentary-like feeling. Adding to that sensation, the characters are introduced through their Wiley high school IDs. It’s a neat way of conveying how identities and expectations are formed through social systems. The film beautifully juxtaposes their school identities with who they are, and who they want to be, beyond such constructs. With a freewheeling approach, the Ross Brothers show a great deal of endearment towards letting the youth speak for themselves. Part of the conflict that arises in coming-of-age films is teenagers not being listened to. Those feelings of being unseen and unheard are combatted by a keen observation of Gen Z dynamics. From dialogue and articulation, to ways of relating with one another, the film admirably sets out to capture authentic generational experiences. In a standout scene, a skateboarder who meets the central teen group empathizes with their desire to get out of their town. He couldn’t stand his town either, and his parents couldn’t hold him back from doing what he loves. This moment intersects with a recurring theme of the film: new beginnings. As soon as the teenagers hit the open road, their possibilities feel endless and vast. With a film of this nature, the needle constantly moves in its narrative focus. The meandering pace can sometimes lose your attention, but that wandering eye also works as the film’s strength. The story focuses on characters less individualistically and more as a collective. They are a spirited burst of feelings, moments, and experiences that flow freely into one another. The film occasionally uses narration to personalize some characters; for instance, one of the teens speaks on growing up quickly and caring for his younger siblings without the help of their parents. Hearing of the formative responsibility he carries makes his search for identity all the more profound. The youth of Gasoline Rainbow figuratively and literally get the open space to roam free and discover themselves, a refreshing change of pace in modern social media-driven terrain. The handheld direction encourages an unfiltered environment for them to absorb real settings and engage in spontaneous interactions. The use of setting and location help to establish a candid tone and atmosphere. Vast landscapes of pink-orange skies capture a far-reaching horizon and the feeling that anything is possible. The Ross Brothers’s cinematography finds a stunning cinematic angle to everyday settings, from a cafe parking lot to a stranded van on the open road. As well, the film’s soundscape is an eclectic absorption of what the teens are listening to, and which pieces of music can elicit a specific mood. From asking Siri to play Howard Shore’s “The Shire” from The Lord of the Rings, to the use of Debussy’s “Clair de Lune” as they finally reach the Pacific shore, music plays a reflective role in capturing the various sounds of a generation. While Gasoline Rainbow loses some focus with a meandering structure and slow pacing, the film has a poignant conclusion once the teens reach their destination and are faced with the reality of what to do next. Will they traverse back to Wylie and get “real jobs”? Or will they find a course off-route and divert from what everyone back home expects from them? The film strikes an impressive balance between how the teens interact with expectations, and how they navigate the independent thoughts swirling in their minds. Gasoline Rainbow finds a spirited adventure in its timeless homage to being young, wanting to discover the world at your feet and determine your place in it. Daniel Craig in Glass Onion: A Knives Out Mystery (2022) Calling all hungry detectives! In collaboration with Netflix, Secret City Adventures is bringing a Knives Out-inspired dinner to Toronto for the first time, and you can have an exclusive bite. Set in Rian Johnson’s mysterious Knives Out universe, The Perfect Bite promises and delivers on an evening full of delicious meals, with an interactive whodunit twist. From acclaimed Chef Maribelle Moore comes a 4-course set menu carefully dedicated to the untold story of her dearest friend, Noah Johnson. The menu contains secrets about Noah and the Salty Six, a culinary group formed by Maribelle and fellow chefs while they were all students. Each dish has a hidden message for dinner guests and their table mates to solve, bringing them one step closer to unlocking the mystery of The Perfect Bite. As the guests are wined and dined, key players from the Salty Six emerge to make everyone feel part of the story. The moment you arrive on the scene, tucked away in Toronto’s mainstay Peter Pan Bistro, enthusiastic actors whisk you into their world of the culinary elite. Committed performances are just a few of the ingredients that make The Perfect Bite a satisfying experience. Guests are sat in groups of four and work together to decipher the clues in each dish. The mystery elements are incorporated into the food so creatively. Cutting into the Amuse Bouche — a sweet pea risotto — reveals cheesy layers of truth. This sampler gets the ball rolling for more intricate dishes; a mushroom mousse appetizer, a duck confit entree with a twist of seasoning, a fluffy palate cleanser, and a “berry” delicious sous vide cheesecake to finish. Photos by Nadia Dalimonte The mix of delicious food and whodunit puzzles is a truly sensory experience, one that works your brain and satisfies your taste buds at the same time. The puzzles are easy to grasp, fun to decipher, and have enough twists and turns to keep you guessing. The dinner service is well-timed and adds to the flow of a smooth evening. Some of the plating is a playful nod to the murder mystery genre, in particular the pastry cigar filled with mushroom mousse, a dish fit for a detective. The menu also accommodates vegan, vegetarian, dairy free, and gluten free dinners. From the delectable food and inviting ambience, to the immersive mystery elements, The Perfect Bite is a stimulating night out that leaves a lasting impression, down to every last bite. Whether you’re planning a creative date with your significant other, or a gathering with family and friends, Secret City Adventures has you covered. But not for long…tickets are selling in hot flashes. Savour the moment and get ready for a dinner like no other. Your mystery table awaits! The Perfect Bite opens at Peter Pan Bistro in Toronto on May 16 and has been extended to run until July 28. Visit www.knivesoutdinner.com for tickets. Photo by Nadia Dalimonte

Lily Gladstone in "Under the Bridge" (2024) Victims of many true crime stories in film and television lack characterization and humanity. Often young women in these narratives, the question of who they were beyond a statistic remains largely unanswered. The stories tend to focus on who committed the crime, using the whodunit element to build suspense, while the interior worlds of the victims go underrepresented. Names and faces become headlines, archived in a constantly changing news cycle. The Hulu limited series “Under the Bridge” pulls from the archives to respectfully dramatize one of the most horrific true crime stories in Canadian history. On November 14, 1997, fourteen-year-old Reena Virk attended a party in Saanich, British Columbia and never returned home. Following the murder, a violence prevention campaign emerged from Reena’s parents, encouraging the BC government to introduce anti-bullying programs into schools. Developed by Quinn Shephard and based on Rebecca Godfrey’s book of the same name, “Under the Bridge” explores the backstory of Reena (Vritika Gupta) in the context of intergenerational relationships, systemic bullying, and the devastation of broken homes. For many kids navigating their teenage years without a healthy family foundation, emotions like anger and anxiety have no place to go except inflicted on others. It is a brutal cycle Reena finds herself cornered into, and she wants to make the bullies feel as bad as she does. Series co-director and co-writer Quinn Shephard makes a compelling effort to try and understand who Reena was as a person. Like most teenagers, she felt frustrated living at home and being told what to do by her parents, Indian immigrant Manjit (Ezra Faroque Khan) and Indian-Canadian Suman (Archie Panjabi). Reena craved acceptance, and found a corrupted version of it outside her flawed but loving family. The viewer also gets to know Reena through the impact of peer surroundings, mainly the girls of the Seven Oaks Youth Home. Nicknamed “BIC” for being labelled as disposable (like the lighters), these girls form a gang to look out for each other, because they have no one and nowhere else. The gang includes leader and John Gotti worshipper Josephine (Chloe Guidry), her terrifying best friend Kelly (Izzy G), and fellow youth home resident Dusty (Aiyana Goodfellow). Josephine and Kelly are the biggest instigators of the group. They call themselves the Crip Mafia Cartel (CMC) and build a foundation on vicious intimidation tactics to survive. Dusty is kept on the outskirts of being a true gang member. Josephine and Kelly manipulate her vulnerable state of mind to get whatever they want, ultimately extending the same behavior towards a shy Reena. Their faux acceptance fills Reena’s loneliness. It is heartbreaking to watch her soul gradually deteriorate at the hands of so-called friends, who are lost and broken themselves. As Riley Keough’s Rebecca Godfrey states, “Young girls in Victoria were the ones we were supposed to protect, not be protected from.” There are several layers to this narrative beyond a girl falling into the wrong crowd. “Under the Bridge” takes a ground-level approach in its inclusion of teenage perspectives. On a more resonant level, the series focuses on authoritative figures in the areas of law enforcement, journalism, and parenthood. Lily Gladstone plays police officer Cam Bentland, an Indigenous woman adopted by her father, police chief Roy Bentland (Matt Craven). Cam takes the lead investigator role on the murder case, bringing immense sensitivity and urgency to finding Reena. Having grown up knowing the feeling of abandonment, Cam also identifies with the Seven Oaks girls. Her presence is a beacon of hope for justice, and a voice of reason speaking out against racism in Canada’s police force. Her character also ignites a needed conversation particularly around Indigenous Canadian history. Lily Gladstone anchors the series with a sublime, thought-provoking performance that immediately draws you in. From Kelly Reichardt’s “Certain Women” to Martin Scorsese’s “Killers of the Flower Moon,” quiet intensity has become a defining quality in Gladstone’s work. Their sensitivity as an actor lends exceptionally well to the role of Cam. Gladstone conveys the weight of many resonant themes at play, from the struggle for acceptance in this position of power, to fighting for justice in a racist environment that also does not take rebellious youth seriously. Gladstone shares authentic chemistry with each of their co-stars, among them Riley Keough who plays author Rebecca Godfrey. In the series, Rebecca begins writing her book called “The Misunderstood Girls of Victoria,” which would go on to become “Under the Bridge.” After years of living in New York, she returns to find Vancouver Island haunted by her own tragic memories and overwhelming guilt. The closer she gets to the girls of Victoria, and ultimately the murder case, the deeper her reconnection with an old friend: Cam. Together they find a mutual benefit — Rebecca gets material for her book, while the trust she earns among teens provides Cam with insider case-related knowledge. Rebecca and Cam feel sympathy towards the teens on different levels, which brings alliances into question and complicates their dynamic. Both perspectives are so fascinating to watch, in that they are navigating conflicting stances when it comes to defining justice for Reena. Following her Emmy nomination for “Daisy Jones & The Six,” Riley Keough returns with another impressive performance that exhibits her understated and intuitive qualities. She balances a poignant backstory with a self-awareness in her character being the one to tell Reena Virk’s story. While Keough does not get a whole lot of material to explore, it makes sense for the author to be more of a footnote here. “Under the Bridge” has a bigger narrative picture at play, where much of the supporting cast shine. Vritika Gupta in "Under the Bridge" (2024) Reena’s parents Manjit and Suman, played brilliantly by Archie Panjabi and Ezra Faroque Khan, bring a significant amount of context and emotional resonance to the story. They too get layered backstories, which adds weight to one of Reena’s lines: “My story began long before I got here.” To understand her, the viewer goes back in time with her parents. Panjabi is one of the biggest standouts of the cast. She gives the most impressive performance of her career as a mother utterly heartbroken by the void in her family picture. Her emotional rollercoaster is so lived-in, you feel as though you are sitting right next to her through the entire ordeal.

The young cast also impresses throughout the series. Vritika Gupta gives a commendable performance as Reena and brings complex humanity to this role. You want to reach through the screen and stop her from meeting such poisonous influences. Chloe Guidry and Izzy G are terrifying as the troubled best friends Josephine and Kelly. Their unpredictable intensity makes each scene nerve wracking to watch. Aiyana Goodfellow shines memorably as Dusty, and has some of the most morally haunting moments in the series. The teens' shared chemistry is terrific and adds to the overall emotional pull of the storytelling, which balances various perspectives that maintain attention. As well, their individual abilities to test the grey areas of humanity make you absolutely loathe their behavior, and yet still feel pangs of sorrow and sympathy towards (most of) them. A recurring theme that stands out in “Under the Bridge” is how impactful it is to have beams of support, people who love and care about you, and want what is best for you. Whether such support comes from chosen families, or families we are born into, the significance of that togetherness comes through, and its absence is strongly felt. What makes the series even more heartbreaking than it already is, Reena had this family life, but was so overcome with loneliness, and shown manipulative affection by kids who are missing real affection in their lives. As Suman (Panjabi) explains, to understand who Reena was is to understand the mindset of those who took her soul, and ultimately her life. In mass media, victims of true crime are often limited to public perception and become defined by their tragic endings. The series adheres to the idea that stories have no definite endings or even beginnings. Reena’s story does not begin and end with murder, making “Under the Bridge” more than just another entry in the true-crime genre. “Under the Bridge” premieres on Disney+ in Canada on May 8. By Nadia Dalimonte George MacKay and Léa Seydoux in The Beast The power of what it means to be human is put on ambitious display in Bertrand Bonello’s The Beast, a hypnotizing sci-fi odyssey that spans time and space. Adapted from Henry James’ 1903 short story The Beast in the Jungle, Bonello swirls a techno future with a contemporary Lynchian L.A. noir and an Edwardian era love triangle. At the core of these intertwining worlds is Gabrielle Monnier (played by Léa Seydoux), a woman who lives in perpetual fear that something catastrophic will happen. Gabrielle’s fear dates to 1910, around the Great Flood of Paris, when she was a married pianist in mysterious liaisons with an Englishman named Louis (played by George MacKay). The two characters’ first meeting feels akin to déjà vu. Surely their paths must have crossed elsewhere, whether “elsewhere” is reality as we know it, or another version fueled by subconscious drives. Bonello’s film is concerned with losing the beauty of reality and the varied spectrum of emotions, good or bad, that make us human. The fear of not feeling things, and the manipulation of that fear by artificial intelligence, makes The Beast a startling modern day horror story. In Bonello’s version, the beast is brought out of the jungle and into a bleak dystopian future.

The Beast sets the stage with a futuristic concept that is both technologically advanced in its practices, and hauntingly realistic in its ideology. Partly set in 2044, the story takes place in a society where everyone’s lives are dictated by artificial intelligence, and human emotion is considered dangerous. To achieve neutrality, citizens purify their DNAs by undergoing a “purification” procedure that deletes centuries-old inherited trauma. Past lives are eradicated to cleanse human beings of emotion, so that life can be surface-level and free of complexities. When Gabrielle undergoes the procedure, she is faced with simulations of her past lives, among them an esteemed pianist in 1910 Paris, and a club-hopping house sitter in 2014 Los Angeles. In each decade, she encounters different versions of Louis (MacKay). The film introduces his character at a 1910 high-society party, where he exudes the energy of a tempting and passionate suitor. Yet there is something about his interactions with Gabrielle that carry an aura of impending disaster, as though another version of Louis is lurking in the shadows, ready to pounce. The 2014 storyline drags the most horrific version of him into the light: Louis Lewansky, a 30-year-old virgin of incel ideology who vlogs about how magnificent he is, and that women deserve to be punished for not being with him. Through this despicable character, Gabrielle still senses her past lover buried deep within; for instance, after an earthquake rattles the streets of L.A., she notices him outside her temporary home and invites him inside. The film leaps through time to show how “the beast” takes on many different forms. Bonello first uses a green-screen environment to frame the story. It is unclear whether Seydoux is playing herself, or simply another version of Gabrielle, as she is instructed in a scene to act afraid of something that doesn’t really exist. Her palpable fear in this introductory scene sets the tone for a recurring sense of dread. Whether in the form of a natural disaster (flood; earthquake), a technological disaster (cyberattack), or a man-made hell (Louis Lewansky), fear ravages through The Beast like a plague. On the surface, the film presents as a sci-fi romance about two lovers reconnecting across space and time. Buried in the passion and yearning lies a deeply unshakable horror story about artificial control and existential dread. Continuing a page in the book of many great horror films, Bonello grounds horror in real fears. The film explores the beasts that we cannot see, hiding in plain sight. Much of what Bonello has to say involves the concerning rise of artificial intelligence, particularly the replacing of humans to generate images void of real emotion. The 2044 storyline is populated with dystopian designs and muted expressions. An invisible substance cloaks the air, prompting Gabrielle to wear an enhanced face mask outdoors. The “purification” centre is surrounded by buildings marked with a year – 1972, 1980, 1963 – and each space has a disco with era-themed music. In Bonello’s future, lives of the past are within easy reach. Most of the scenes are visions of Gabrielle’s past that she experiences during the procedure. In reliving these moments, she becomes torn between wanting to continue living out the past and being fearful of spoiling the present. The play on time travel is a fascinating subversion of storylines that often populate the sub-genre. The story moves back in time not to change something from happening, or to analyze the ripple effect of one incident, but to hold onto what it means to be human. The dread that Bonello explores is that of losing emotions, and reaching a point where artificial intelligence causes a new way of life. Gabrielle speaks of such dread when she reveals, “I’m scared of not feeling things.” Whether good, bad, or everything in between, emotions make us feel alive. To love is to feel, and the romance between Gabrielle and Louis goes against all odds to survive a bleak future. Bonello’s vision for The Beast is brought to life by a spectacular Léa Seydoux as Gabrielle Monnier, the film’s protagonist. Seydoux has the complex role of playing different versions of the same character, across various time periods, within an unconventional narrative structure. The story can be muddled and tricky to fully understand, but the majority of The Beast finds a steady anchor in Seydoux. The role plays to her incredible strengths of timelessness and emotional vulnerability. She carries just as much persuasiveness in the 1910s as she does in the 2010s and 2040s. Seydoux also establishes a powerful heart line that connects all these versions, so that they feel part of one entity. Gabrielle’s heartache for humanity is transfixing to watch, as is her chemistry with George MacKay, who plays her lover scattered across time. MacKay is an actor of impressive range, and he flexes his chameleonic muscles as three versions of his character Louis. The 2014 timeline in particular gives MacKay the most material to work with. He delivers a truly unnerving performance as Louis Lewansky that keeps you in a perpetual state of fear, and leaves you with the depressing fact that many versions of this character exist in real life. The Los Angeles narrative in its entirety gives interesting context to the film overall, while also working as an effective horror standalone. The classical music adds to the nightmarish quality. The Beast marks the first soundtrack composed by both Bertrand Bonnello and his daughter Anna. Together they’ve crafted a mix of intense sounds that can shape a sweeping romance one moment and cut the tension of a murderous spree the next. Much of the imagery also lends to the nightmarish feeling of the L.A. narrative. One of the most frightening scenes takes place in a video call exchange between Gabrielle and an online psychic, while a dangerous figure looms around the house. The psychic, who initially appears in the 1910 timeline as a fortune teller, has an extremely Lynchian quality, from her surreal mannerisms to her ominous dialogue. Even in the face of potential danger, her tone is eerily neutral. In a 1910 scene between Gabrielle and Louis, Louis refers to the doll factory that Gabrielle’s husband owns, and questions why all dolls have the same expression. Their faces are neither happy nor sad, just neutral. The subject of neutrality is often explored through the recurring symbol of dolls in The Beast. The 1910s lay the groundwork, followed by a modern talking doll in the 2010s, and a life-size companion doll (played by a tremendous Guslagie Malanda) in the 2040s. Malanda’s character encourages the endless possibilities of artificial intelligence (“I have many options you know, make the most of me”). This companion can be anyone and anything to Gabrielle, but nothing can recreate the real emotions that Gabrielle fears losing. The Beast is full of bold ideas and grand executions. While the story is not the most coherent to follow, the creative vision puts you in a compelling trance nonetheless. Bonello wraps the intense fear of love with an ambitious sci-fi tale of 20th century affairs, contemporary horror, and a future that isn’t so fantastical. The dependency on technology and advancements of artificial intelligence put humanity in an increasingly vulnerable position. But human emotions are impossible to shake. The Beast tells an expansive, daring tale about what it means to really be alive. The Beast arrives in theatres in Toronto and Vancouver on April 19. By Nadia Dalimonte Kate Winslet in HBO's The Regime The magic formula of pairing Kate Winslet with an HBO series has been tried and true. 2011’s period melodrama Mildred Pierce from visionary director Todd Haynes won 5 Primetime Emmys, including Lead Actress in a Miniseries for Winslet’s starring titular role. A decade later, 2021’s detective mystery Mare of Easttown from creator Brad Ingelsby won 4 Primetime Emmys, among them a Lead Actress win for Winslet’s lovable Mare. Her performance struck an emotional chord and infused you with a sense of wonder as to what became of the small-town detective. The graceful end to her chapter beautifully stuck the landing. While we may never get another season, understandably so given it’s a limited series (a distinction that’s been played around with as of late), this void left behind can be filled by yet another electric pairing.

HBO’s six-part limited series The Regime, from the producers of Succession, pulls compelling satire from a thinly veiled authoritarian regime. Winslet plays Chancellor Elena Vernham, a delusional dictator of a fictitious country in “Central Europe” whose power begins to unravel. Elena’s synthetic-looking palace, complete with leopard print accents and an underground disco, has become a bubble of her own creation. The clinical palace walls have housed everything from her hypochondria and paranoia to bizarre social media livestreams and meetings broadcasted live from her bathtub. After some time in this absurdist loop, Elena finds a fix for her boredom: Herbert Zubak (Matthias Schoenaerts), a disgraced corporal and assassin who becomes her confidant, and maybe more. With Zubak by her side, the Chancellor finds new ways of exercising her power within the palace and carefully maintaining her image to the country’s people, who she collectively refers to as “my loves.” But her obliviousness to what real people need, and the human rights issues they face daily, is alarmingly dire. Zubak’s growing impact on the Chancellor walks a fascinating tightrope between appeasing to an out-of-touch figure of authority and undermining it for the good of the country. Her grounds for decision-making operate on fear, and a deeply embedded trauma that the series dodges. Elena is a character who always thrives from power, which allows for Zubak’s volatile commands on her behalf to be tuned up at maximum volume. Their dynamic moves to the rhythm of an old rollercoaster where every wobble and creak can be heard. Watching them both navigate a power struggle within their own relationship is dynamite. As executive producer and lead performer, Winslet excels at capturing the darkly comic tone that runs through the veins of The Regime. The world is not ready for how much fun she has bringing Elena Vernham to absurdist life. This character gives one of the most accomplished and versatile actors, decades into her career, a playground to flex brand new muscles. Following up the protective hardshell of a tragically real Mare Sheehan, with a woman so far removed from any semblance of real life, is a thrilling testament to Winslet’s talent. Her sense of humor is also on full display; Elena is far and away the funniest role and performance of her career. From punchy one-liners and singing deliberately out-of-tune, to an entertaining display of physical comedy. The supporting cast rounding out The Regime include Matthias Schoenaerts, brilliantly cast in the role of Zubak. Not only does he balance the intensity of this character’s physicality and stamina, but also the emotional needs that anchor his decision-making. Zubak is hardwired to equate love with pain, which influences his relationship to the Chancellor. While the writing does not flesh him out enough as Elena, leaving more to be desired, Schoenaerts brings a compelling presence to the screen and shares both frightening and amusing chemistry with Winslet. Zubak takes up most of the space around Elena, as her husband (an endearing Guillaume Gallienne) watches on. Other characters operate much like Elena’s husband, mere observers to the madness. Andrea Riseborough, while great as usual, unfortunately does not get as much material to work with as hoped for. The same can be said for Martha Plimpton and Hugh Grant, electric in their roles but missing the opportunity to pack a bigger punch. The Chancellor is the primary source of entertainment in The Regime, and the writers know it. The screenplay smartly focuses on Elena’s character development with an understanding of her performative nature and the sublime talent that Winslet brings to the table. The character’s grip on power is tumbling down in real time, and yet she puts on a bubbly face without a care in the world. Her surrounding government officials propose a ration program to combat the threat of starvation, to which a bored and frustrated Elena responds, “This is Central Europe, no one is starving!” Horrors are unfolding before her very eyes, but her obliviousness knows no limits. The series somehow finds a steady-enough balance between enjoyable and nightmarish. For every biting line, lies a sinister undertone that only grows more powerful. It’s a surreal experience, and the absurdity can be felt from all angles. Whether it’s the exaggerated production design and vague accent work, or the horror-fueled score and the caricature-like people who populate the palace. Most of all, the absurdism radiates from Winslet’s performance, an insanely funny combination of cruelty and pleasure. The Regime airs Sunday March 3 on HBO. By Nadia Dalimonte Daisy Ridley in Sometimes I Think About Dying Sometimes Fran likes to think about dying. Not necessarily because she wants to, but out of morbid curiosity. How would it feel to hang off a crane? To drink poison? To lay alone in a forest, so far removed from the physical world? Thoughts of death occupy the frontlines of Fran’s mind as she goes about her work day at a drab office in coastal Oregon. While co-workers give weight to water cooler conversations, she awkwardly keeps to herself and watches in silence on the sidelines. But all that changes when she meets Robert, the new employee with whom she feels an indescribable spark. As their conversations evolve from spreadsheets and emails to movies and relationships, Fran faces the ultimate test: will she feel comfortable enough to let Robert in to her otherwise solitary life? Director Rachel Lambert finds a confident rhythm with Sometimes I Think About Dying, a compelling gem in the “less-is-more” corner of storytelling.

Carrying the film with striking impact is an incredibly restrained Daisy Ridley. With every little glance, she lets the viewer pick up on her character’s hesitance of those around her. She might be seen as invisible by her co-workers, but her personality stands out in the moments of awkward silences. During a meeting where colleagues are asked to introduce themselves followed by their favorite cheeses, Fran matter-of-factly states that she likes cottage cheese. In the stillness that washes over the room, she catches the attention of Robert (Dave Merheje), unbeknownst to her. The two strike up a virtual office chat afterwards, and a new layer of Fran is explored. Ridley’s performance acts as a gentle guide through this character breaking out of her shell with the hope that she will be understood. Crucial to the film’s staying power, Fran’s introversion is explored from a perspective that recognizes how much she tries to interact in social situations. She listens intently to the conversations happening around her, as though deciding at what point she ought to join in. While sticking to the wallpaper of a social interaction, she still lets her presence be known, even if her colleagues refuse to acknowledge it. With the introduction of Robert into her life, she opens up in ways that one would not expect and delights in the opportunity to be known by someone else. The story’s mundane office setting adds another layer to how impactful her delight is. Robert’s presence lights up an otherwise draining, monotonous environment for her. It’s in the moments left unsaid between them that she develops a connection, and in their voiced one-on-one conversations that she finds a way to let her guard down. The journey to that point is not an easy one for a character of Fran’s sensibility, which the film depicts with striking relatable qualities. Fran and Robert’s relationship evolves in a refreshingly honest way that puts weight on both of their roles; her attempts at letting him get to know her, and his embrace of the time it will take to reach that level of understanding. Sharing the screen with Ridley, Dave Merhe brings exceeding warmth and charisma to his character. From his passion for movies to the way he lovingly teases Fran, Robert is an endearing personality whose directness and honesty help give Fran some clarity about what she wants. Their melancholic final interaction in the film would not hit as hard emotionally without Merhe’s understanding of how Robert’s presence makes Fran feel. As well, the chemistry between Ridley and Merhe accentuates the initial butterflies that swell on first dates and the early process of getting to know someone. Whether Fran can trust Robert with opening up, sharing her fears and desires, gives the film a strong narrative focus. In addition to Ridley and Merhe’s performances, an unsung standout of the cast is Marcia DeBonis as Carol, the employee who has reached her last day at the office. DeBonis, one of the most prolific character actors in the industry, brings an immediate warmth to the film. Her naturalistic work builds to a compelling moment between Marcia and Fran in the final act, which calls out a depressing reality. For all the work people put into their jobs, they can miss out on life, and most of all the loved ones they choose to spend it with. DeBonis’s understated work speaks to the very human need to be included. Whether it's an office setting where one can present the most conversational version of themselves, or a personal vacation where one can release from mundanity. While the pacing of Sometimes I Think About Dying add to the dreary atmosphere, it also maintains a sense of repetitiveness to a slight fault. It may not come as a surprise that the film is based on a short of the same title, written and directed by Stefanie Abel Horowitz. Stretched into feature length, the nuances of Fran’s introverted experience navigating love and work feel too drawn out for the purpose of filling in space. One too many scenes of Fran zoning out at the office make the film feel overlong in its runtime. Once the relationship between Fran and Robert kicks in, the story takes on a more dynamic shape. Helping to break up the office mundanity is the film’s use of imagery and sound. Whether a long take focused on a crane, or a shot of a “deceased” Fran laying in the forest, the visuals are a vivid reflection of her mind. As well, the use of music conveys the feeling of watching a fairytale and constantly hoping the best for Fran. Dabney Morris’s original score has the sounds of a sweeping romance. Adding to the fairytale is the choice of including a poignant tune from 1937’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. “With a Smile and a Song” arrives at a point in the Disney film when Snow White reassures the forest animals not to worry, she won’t leave them. She asks the birds what they do when things go wrong, and the birds sing a song. The use of this Disney tune in Sometimes I Think About Dying not only builds on the film’s recurring forest imagery, but also adds a thought-provoking layer to where the story leaves Fran. Her realization that Robert doesn’t know her at all, and her willingness to change that, is a sweet embrace of someone working their way through loneliness. Sometimes less is more, and in focusing on Fran and Robert’s serene embrace, as forestry surrounds them, Rachel Lambert creates a rich vision of the central character’s growth. She finds a way to let Robert in. By Nadia Dalimonte Camilla Morrone and Joe Keery in Marmalade The heist romance sub-genre is given a peculiar spin in Keir O’Donnell’s directorial feature debut Marmalade. The film wastes no time getting right to the story of Baron (Joe Keery) and Marmalade (Camila Morrone), an ill-fated couple caught in a whirlwind of robbery. But the couple’s relationship manifests out of thin air, as do their individual motives and what drives them towards each other. Character development gets lost in the whiplash of hasty editing and questionable narrative choices, all of which the mostly reliable cast can’t quite rise above. From the underdeveloped central romance and subplots, to the uneven pacing, Marmalade doesn’t reach that sweet spot of balancing what makes both the romance and the crime compelling.

Marmalade starts with a recently imprisoned Baron and his newfound friend, cellmate Otis (Aldis Hodge). What starts as a cryptic chat turns potentially fortuitous for both of them. Baron has a secret stash of money hidden outside the prison walls. If Otis can help him escape, that money will be free for the taking. To explain how and why this money exists, Baron turns back time to explain how he met Marmalade (Camila Morrone). The two quickly fall in love and plan a Bonnie and Clyde-style bank robbery to kickstart a new dream life together. In the midst of scheming, Baron also cares for his sick mother, whose identity remains a mystery throughout the story. There is more to Marmalade than meets the eye, but the reveals add more confusion than enlightenment on what the intention is. The performances, while mostly committed to O’Donnell’s storytelling, offer no real insight into who these characters are beyond their actions. Joe Keery of Stranger Things fame has an expectedly charming screen presence as Baron. He gives weight to the character’s dumbfounded, seemingly clueless qualities. Keery also manages to balance the film’s odd tonal shifts that take the character on an unexpected journey. The choices O’Donnell makes to reach those unexpected moments, however, make the entire journey feel convoluted. Baron lacks the reliability and strength to be the anchor of this story. From his rushed character development, to underwritten relationships between those in his orbit. Sharing the name of the title, Camila Morrone’s Marmalade is one of the more peculiar elements of the film. Her colorful introductory scene is full of promise and injects a mysterious energy into the story. She appears out of thin air, to the extent that one might question whether or not she is a manifestation of Baron’s imagination. Marmalade is a picture of danger to him. The two’s budding relationship presents the opportunity to embark on an adventure so far removed from his mundane existence. What each character aims to get out of the opportunity poses more questions than answers. Morrone has shown promising talent so far, from playing the lead role in Annabelle Attanasio’s Mickey and the Bear to giving a standout Emmy-nominated performance in the series Daisy Jones & The Six. On paper, Marmalade is another role for Morrone to challenge her range and find a groove in her acting style. While she brings plenty of energy to the role, her efforts feel misplaced and underutilized. As a result, her character’s presence becomes exaggerated and doesn’t quite hit the mark of intended eccentricity. Morrone fares better in the quieter, more dramatic moments where one can sense insight into her character’s backstory. But that aspect of her unfortunately gets sidelined by the film’s uneven focus. To the same degree, Aldis Hodge tries his best with the material given, but his character Otis also feels underutilized. The film sets up a key connection between him and Baron as cellmates, but that connection quickly becomes a device to move the plot around, and neglects to give Otis a sense of his own purpose. The story of Marmalade jumps from Bonnie and Clyde-style passionate crime, to an undercover prison break, to a complete one-eighty jump in a certain character’s identity, lacking the coherence to hold it all together. The film thrusts the viewer into the narrative without establishing a strong enough sense of place, nor getting to know the characters beyond archetypes. The end result is a mishmash of defining features one would find from a lot of crime-romance films, and not a whole lot of singular vision in the writing or direction. Owen Wilson and Tom Hiddleston in season two of "Loki" (2023) Since his first appearance as the villainous trickster Loki in Kenneth Branagh’s film “Thor,” Tom Hiddleston has become a major staple in the Marvel Cinematic Universe. Hiddleston’s breakthrough role has entertainingly popped up enough times to warrant a Disney+ series centered on the God of Mischief. From show runner and head writer Michael Waldron, “Loki” is set after the events of the Russo Brothers’ “Avengers: Endgame” and is part of phase four of the MCU. Season one follows Loki to the Time Variance Authority (TVA), where he is enlisted to help eliminate a reckless variant of himself that’s been wreaking havoc across time. Loki partners with one of the Time-Keepers, agent Mobius (Owen Wilson), and a high-profile Hunter B-15 (Wunmi Mosaku), to track down the variant: Sylvie Laufeydottir (Sophia Di Martino), determined to avenge the TVA’s erasure of her reality.

The plot spins through Variants and multiverses, and Loki eventually ends up in the wrong timeline. Season two continues where the first leaves off: Loki is in a version of the TVA where Mobius and Hunter B-15 have no idea who he is. Lost in time and space, Loki must navigate an expanding universe to find his alter ego Sylvie. In other words, season one is a narrative prerequisite for season two, a somewhat convoluted experience where action-packed sequences outweigh heart. While the story can get a little too confusing, plenty enough compelling material can be found across the board, from stunning production and costume design to committed performances. The second season finds some improvement on the first with more ambition, and wastes no time jumping into the action. The tense premiere is a promising showcase of why returning to Loki is worthwhile: it’s an enjoyable play on time travel that still retains the complexities of his character. Though in shifting him and others around the multiverse, the season starts to lose key relationship time elsewhere, primarily when it comes to Loki and Sylvie. In season one, her character had become an interesting parallel figure who, as a variant of Loki, holds up a mirror to his internal conflict. The two have a compelling dynamic that can be romantic, platonic, and everything in between. Most significantly, having seen himself only as a villain, Sylvie’s presence has started influencing his self-identity. Loki’s feelings for her are a great source of emotional connectivity to the story, which season two lacks. With Loki and Sylvie on different paths, the story shifts gears towards another duo: Loki and Mobius. Hiddleston and Wilson continue to shine with strong chemistry, and Hiddleston in particular adds yet another set of layers to a character he has perfected at this point. After a decade playing this role, Hiddleston finds new and surprising ways to keep Loki interesting to watch. His sophistication, charm, and commanding presence give “Loki” consistency. Keeping with consistent performers, Wunmi Mosaku and Owen Wilson return with solid work, and Di Martino continues to bring terrific empathy to Sylvie. The show also infuses a welcome addition to the cast: the brilliant Ke Huy Quan as Ouroboros (also known as OB), the TVA’s head of the Repairs and Advancement Department. The character has a tinkering spirit and a passion for fixing things, which plays into one of the more universal themes of the show: repairing, not replacing, the broken. Quan brings delightful humor and charm to the screen. His performance is pure delight in human form. With focus on the time travel elements, season two of “Loki” has a neat visual language with its period production design and evocative costumes. The TVA headquarters in particular have an impressive color palette and scale. The world building, visual effects, and overall production value have character. Practical sets go a long way, bringing a more tangible feeling to the narrative. The overall atmosphere of the show is effective and polished. While season two of “Loki” gets off to a jumbled start, the key ingredients are intact for a thoughtful and ambitious character study. The exploration of time as a means of self-reflection and personal evolvement sets the series apart. Thematically “Loki” strikes a memorable chord, only enhanced by Tom Hiddleston’s layered and resonant performance. The story might be incomprehensible at times, but Hiddleston brings emotional sense to the glorious purpose of it all. “Loki” season 2 premieres on Disney+ on October 5. Jodie Comer in "The End We Start From" “The End We Start From” begins with a calm before the storm. A young woman (played by Jodie Comer) gazes at her pregnant belly, her eyes filled with wonder. Moments later, water seeps through the door of her London flat. Without a moment’s notice, the entire city becomes submerged by flooding. In the midst of environmental disaster, the woman makes it to the hospital and gives birth to her first child. The end of one world gives way to the start of another: the novelty of motherhood. When the woman, her partner (played by Joel Fry), and their newborn are forced to leave London in search of a safer place, they are exposed to the elements of terror and uncertainty. Making her feature directorial debut, Mahalia Belo finds a sensitive balance between moments of calm and panic. Despite some uneven pacing and undeveloped plot points, a remarkable Jodie Comer makes the film resonate as a poetic and muted character study. Grounded by Comer’s work, “The End We Start From” is a gentle post-apocalyptic drama that branches into an intimate depiction of motherhood and existential crisis.

Based on Megan Hunter’s 2017 debut novel of the same name, “The End We Start From” is far more hopeful than many dystopian-set stories tend to be. From the protagonist (Comer)’s befriending nature towards her surroundings, to the uplifting visions she has of her partner when the fate of his character is unknown during the film’s second act. The story has a fragmented structure that effectively frames what the protagonist is going through. As her mind falls to pieces, she holds onto her sense of determination and persistency. She creates a protective bubble around her child, ready to fight for him at a moment’s notice, while also feeling the urge to flee. The film captures these internal perspectives on a strong visual level, from Belo’s observational direction and Suzie Lavelle’s cinematography, to Arttu Salmi’s fluid editing. There is a lulling quality in how one scene flows to the next, with occasional breaks of intensity during moments of impending danger. The delicately filmed opening sequence is a fine example, paralleling intense images of the birth and the flood without becoming too on-the-nose in its metaphorical comparisons. Weathering the storm of “The End We Start From” is a magnificent Jodie Comer, who delivers some of her most contemplative and layered work yet. Her character’s frame of mind acts as a guide for direction, and in the hands of Comer’s talent, the story finds its footing. Comer brings exceptional attentiveness to a new mother’s physical and psychological journey, while also attuned to the environmental changes that push her into isolation. Her presence alone establishes a magnetic connection to the viewer. Comer is the anchor to the film’s non-linear storytelling. From her sense of humor and impromptu expressions of joy, to moments of deep existential crisis where she questions her place in the world, Comer finds the layers to this role. Her processing of extreme change makes for complex material to watch. Over the past 8 years, screenwriter Alice Birch has covered an exciting breadth of material; from 2016’s “Lady Macbeth” (Birch’s film debut) and 2020’s Emmy-nominated “Normal People,” to 2022’s “The Wonder” and this year’s Emmy-nominated “Dead Ringers.” Birch’s adaptation of “The End We Start From” continues in the vein of character-driven stories that speak to women’s experiences amid some sort of collapse, whether societal or internal. Her dystopian screenplay tackles a bit of both – the breakdown of London’s infrastructure, and the disintegration of individual life within it. Comer’s character not only has to face survival on a practical level, but also question where she fits in a new world. Plus, layered within is her constantly evolving journey of motherhood. While the themes are well balanced, the story sometimes moves at an uneven pace and engages in unfocused plot points. Outside of the protagonist’s perspective, the film jumps too far ahead with its introduction of vague supporting characters. When the family finds temporary solitude with her partner’s parents (played by Mark Strong and Nina Sosanya) at their countryside home, the writing of those new characters feels too abrupt to make an impact. Strong and Sosanya are given very little to work with. Faring a bit better is Katherine Waterston’s character O, a mother also in search for safety and whom the protagonist meets at a commune. Waterston brings refreshing spark and charm to the screen, making her role memorable. She and Comer share intuitive chemistry that speaks to their characters’ intense, empathetic bonding. In one of the most endearing scenes of the film, the two of them walk through dirt roads while scream-singing the lyrics of the classic ballad “I’ve Had the Time of My Life.” The film has a missed opportunity by not exploring their bond in further detail, as the buildup to their final scene doesn’t quite hit the intended emotional mark. The film at its core is about a woman figuring out how to be a mother, and rediscovering her sense of self in the process. Despite the dangers ahead, and the potential benefits of her family splitting up to get help, she firmly argues, “We have a baby, we’re a family…we stay together.” Despite clear roadblocks and words of discouragement from others in her path, she desperately tries returning back to London, even if it means giving up safety elsewhere. London is home; without that sense of place and stability in her mind, she feels lost. This is beautifully conveyed in the film’s final act, when she questions to herself, “Where am I?”. Comer’s utter helplessness and disorientation in that moment are stunning to watch. Moments like this speak to the strength of her commitment and the emotional resonance of Birch’s screenplay. Beyond the acting and writing, the production of “The End We Start From” also calls attention to the tone that Belo’s direction goes for. The various sounds of water are captured effectively throughout the film, from intense moments of flooding to raindrops falling onto windows. The sound design builds tension and creates a palpable atmosphere around the characters. The film utilizes a limited budget to impressive results; the special effects have an organic and realistic quality to them, particularly when it comes to rooms being submerged in water. The score by Anna Meredith also stands out; while it does feel out of place in a few scenes, its overall intensity captures the sentiment behind the story. “The End We Start From” may be a little too muted in its approach and uneven in its storytelling, but Comer is such a powerhouse performer that the film simply shines in spite of its flaws. Comer infuses the story with a range of messy human emotions that makes it impossible not to feel connected. Playing a character who tries to find her footing between the impact of crisis and the escape from it, she taps into the film’s resonant themes and guides the viewer on a grounded journey. The power of her work rests most vividly in the moments she leaves unsaid; a single glance can evoke just as much as an emotional speech. Coupled with Belo’s steady direction and an introspective character study, the film finds enough ways to resonate. |

Archives

June 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed