|

Ayo Edebiri and Jeremy Allen White in season two of "The Bear" (2023) When the first season of a returning show captures lightning in a bottle, the question becomes, how will the next chapter live up to its various measures of expectation? Culinary smash hit “The Bear,” created by Christopher Storer, sets the bar high in its first season. A work of fiction feels like a documentary; every ingredient from the impeccable writing to the immersive acting evokes an energy that hooks you in from the start. Jeremy Allen White plays a young chef risen from the ashes, shoved through the world of fine dining, and pulled towards his family’s scrappy Chicago sandwich shop under mournful circumstances. Amidst the kitchen frenzy, however sticky and stressful things get, White’s yearning stares into the distance ground everything into place. This restaurant means something. And because he and the kitchen team have so much stock in the place, every little mishap feels like the entire world is crashing down.

The restaurant’s meaning depends on any given character’s perspective. How do they measure success? Where do they find themselves on the never-ending journey of self-discovery and growth? These are questions that the show smartly continues to explore in its second season, for the bedrock of “The Bear” has always been its characters. From the precise words on the page to the actors who interpret and embody them, their roles are the main ingredient as to why “The Bear” resonates. By building onto them and expanding their personal worlds outside of the kitchen, the writing of season two not only surpasses expectations, but creates a new recipe for success. The boiling, frenetic stress ball of season one is brought to a simmer in season two. Intimate character-driven episodes serve up a mostly soothing departure from clattering pots and pans. That is, until you swim with the Berzatto fishes in episode six… Season two continues the chaos-ridden saga of Carmen ‘Carmy’ Berzatto (White). The environment this time around is more contemplative and slightly less anxiety-inducing. The show picks up where season one leaves off — promising the birth of ‘The Bear’ (Carmy’s nickname), after the closure of ‘The Beef’ which was owned by Carmy’s late brother Mikey (Jon Bernthal). As Carmy and the team clean out shop to create a fine-dining Michelin star-worthy restaurant, they face numerous road blocks along the way, from outdated infrastructure to failed safety inspections. But in the process of starting over, they unearth new layers about themselves. When the pressures of the kitchen are stripped back, so too are the characters inhabiting that space. The writers take them beyond the environment you had been accustomed to seeing them in. Over the course of ten episodes, characters are coming into their own. Their personal experiences, family dynamics, and support systems are explored with a ton of heart, humor, and intensity. From Carmy’s culinary influence on the team, and subtle callbacks evoking the first season, to the ferocious dialogue of a holiday dinner gone sour. Piece by piece, the writers of “The Bear” dig deeper into the characters’ lives while maintaining a recurring theme: it is never too late to have a breakthrough. Every second counts. That has never been more felt than in these standout moments of the season. ***SPOILERS AHEAD FOR “THE BEAR”*** “Pasta” (episode two) Written by Christopher Storer, Joanna Calo, Sofya Levitsky-Weitz Twelve weeks out from ‘The Bear’ opening, Sydney ‘Syd’ (Ayo Edebiri) delivers the news that Tina (Liza Colón-Zayas) and Ebraheim ‘Ebra’ (Edwin Lee Gibson) are being sent to culinary school to sharpen their skills. Tina beams with excitement while Ebra is hesitant. The difference in their reactions — one looking forward to change, the other afraid of it — is a great depiction of the restaurant’s transformative power over the people who help run it. Change and opportunity are spinning by; either you take the leap and fill your sidelines with support, or find yourself behind. Many characters are wrestling between old and new support systems in this episode. During a family dinner between Syd and her father (Robert Townsend), when she shares her excitement about the new restaurant opening and he struggles to take her profession seriously, she reminds him that she is in a different place: one where she is still learning and not alone; she has a partner. Nearing the end of this episode, her partner Carmy and his ex-girlfriend, Claire (Molly Gordon), reconnect at a grocery store. Claire walks into his life when he is on the cusp of newness and in need of positive influence, but he keeps waiting for the other shoe to drop. By introducing this new character, the writing expands on Carmy’s past and evokes the feeling of him being almost frozen in time. As well, the choice to set their conversation by a freezer is a neat example of the season’s strength in planting moments that come full circle later on (in this case, the season finale). “Sundae” (episode three) Written by Karen Joseph Adcock, Catherine Schetina, Christopher Storer Eleven weeks out from ‘The Bear’ opening, Syd and Carmy work on the new menu. Their attempts to figure out which dishes to serve fall apart. After a little too much of this and not enough of that, Carmy suggests that they both go out and try some stuff. They need to reset their palates and find culinary inspiration. But he ditches the plan after an impromptu phone call from Claire, leaving Syd to embark on a solo culinary tour of Chicago. “Sundae” is one of the finest examples of the writers’ love for these characters, Syd in particular as this episode focuses on her perspective. This is where the show’s new recipe for success really comes into play. The gorgeous montages of Syd exploring different foods is an odyssey of her hunger and attention to detail. Sprinkled in the mix, various chefs give her advice that unwittingly sheds light on her relationship with Carmy. The episode marks a strong example of how the writers find moments to reflect on character dynamics. Lines of advice such as, “Make sure you have a great partner, someone you can trust,” or “Listen to your gut” come at the right time. In building the menu with Carmy, Syd has just as much say on the direction of ‘The Bear’. Whether he also truly believes that is called into question. “Honeydew” (episode four) Written by Stacy Osei-Kuffour, Christopher Storer, Sofya Levitsky-Weitz In the running for season two’s best episode is “Honeydew,” an emotionally intimate half-hour of pastry chef Marcus (Lionel Boyce) challenging himself. Upon a suggestion from Syd, who recognizes the need to empower her fellow chefs, Carmy sends Marcus on a Copenhagen trip to gain exposure and sweeten his dessert game. In Denmark, Marcus is trained by British pastry chef Luca (guest star Will Poulter), an old friend of Carmy’s and a walking example of precision. Luca's technique is delicate. He operates in stillness, the polar opposite to what Marcus is used to back home. “Honeydew” lovingly expands on Marcus’ character, impressively combining bits of his past, present, and budding future all in one. As written in the first season, Marcus always possessed an eagerness to create, and a desire to improve. Season two charts Marcus’ journey from a ‘clock in and out’ job to nourishing his career as a pastry chef. Additionally, “Honeydew” marks the first time Marcus opens up about his mother who is ill (season two begins with him by her side in a hospital). You could feel the weight on his shoulders when he visits Copenhagen; as he soaks in his new experiences, he makes a point of sharing his thoughts with her, even if she is unable to respond. “Pop” (episode five) Written by Sofya Levitsky-Weitz, Christopher Storer, Karen Joseph Adcock One can only hope that season three is full of even more self-contained character-driven episodes, because Tina deserves her big moment. While the first season portrays her as having a chip on her shoulder, season two expands on the character through means of various opportunities. After Syd offers her the role of sous chef, and she attends the culinary arts training program (for which Carmy lends his knife), Tina has a more noticeable sparkle in her eyes. She is stepping into the potentiality of a new role with increased confidence and an inspired spirit. This training not only influences her career but also her social life; upon showing up to a gathering her fellow trainees had invited her to, Tina takes the mic at a karaoke bar and stuns with a heartfelt rendition of the song “Before the Next Teardrop Falls.” Moments like this are a prime example of stellar acting and character development coming together to create magic. “Fishes” (episode six) Written by Joanna Calo, Christopher Storer, Sofya Levitsky-Weitz Following the palate cleansers and appetizers of episodes one through five, the main course of the season is “Fishes,” a bitter and fiery holiday time-capsule. The writers take you back a few years to a heated Berzatto family dinner that descends into a traumatic nightmare. What family dinner doesn’t have underlying tension on the brink of explosion? Carmy, Mikey, their sister Natalie (Abby Elliott), ‘Cousin’ Richie (Ebon Moss-Bachrach), Uncle Jimmy (Oliver Platt), and a nervous bunch of relatives (played by a star-studded guest cast) join forces for Christmas with the family matriarch, Donna (guest star Jamie Lee Curtis). This flashback episode gives remarkable context to the behaviors and dynamics between Carmy and his family across both seasons. The overlapping flow of dialogue and buildup of tension creates an environment that rivals season one’s kitchen disaster “The Review” when it comes to inducing anxiety. The incredible writing of “Fishes” hits home how the show has always been in service to its characters. Each and every detail counts. “Forks” (episode seven) Written by Alex Russell, Christopher Storer, Sofya Levitsky-Weitz In the season two premiere, Cousin Richie asks Carmy, “You ever think about purpose?”. The loaded question (and the time it would take to be addressed) drives Carmy away, until he notices the look of defeat on Richie’s face. In season one, Richie was the loudest voice in the kitchen. Season two meets him in an existential crisis. Feeling as though he has not accomplished anything, he questions where he belongs, just as the sandwich shop he had helped run is getting a facelift. Richie’s frame of mind makes episode seven all the more satisfying and inspiring. In “Forks,” Richie is sent to stage a three Michelin-star restaurant in Chicago. After days of polishing forks in a cold-looking kitchen, he moves up the ladder to shadow the pristine front-of-house staff. He also gets to meet the restaurant’s mysterious chef Terry (guest star Olivia Colman). Richie’s apprenticeship opens up a world of possibility; suddenly he sees a potentially rewarding path to follow, particularly in the business of hospitality. Whereas season one sees the characters in ‘fight or flight’ mode, just trying to survive back of house, the writers make an interesting shift towards front-facing hospitality. The season focuses intently on characters such as Richie, working on themselves and in turn, becoming of better service to others. “The Bear” (episode ten) Written by Christopher Storer, Kelly Galuska, Sofya Levitsky-Weitz Overall, this season follows a more simmered down recipe in comparison to its predecessor. But it wouldn’t be “The Bear” without scenes of non-stop stress against the tick of a clock. In the finale, family and friends are invited to celebrate the opening of ‘The Bear,’ a fine-dining experience accumulated from months of training and renovating. The team make a fresh start with some new practices: Richie’s ‘note passing’ communication method taken up from his apprenticeship; Carmy and Syd’s temper-diffusing physical signaling of “I’m sorry,” which Tina observes and uses later on. But old patterns are hard to shake, and nobody can relate to that harder than Carmy. From the beginning of the series, fixing the restaurant is what he always set out to do, and he did not need a reason more sufficient than it being his birthright. Fast forward to the season two finale, and the sentiment of this culinary responsibility consuming him has never been clearer. When an unexpected obstacle forces him to self-reflect in isolation, he simply cannot let go of being that person who keeps all the plates spinning. The writing of Carmy, as well as White’s deeply present and emotionally articulate portrayal, reaches new heights. What does the restaurant really mean to him? How intertwined are his measures of success with his definitions of self-worth and relationships? When the pressure of the kitchen is stripped away, so too is Carmy, trying to understand his place in all the routine chaos he has been living in. In a monologue played tremendously by White, he speaks of failing everyone around him. He resists letting something potentially good happen to him, which recalls his mother’s opinion of herself (not being deserving of goodness) in the “Fishes” episode. When the show leans into quieter moments such as this monologue, it showcases how the writing captures full-circle expressions of character. All it takes is one line — “No amount of good is worth how terrible this feels” — to realize just how much of a cyclical grip Carmy’s traumatic past has on him.

0 Comments

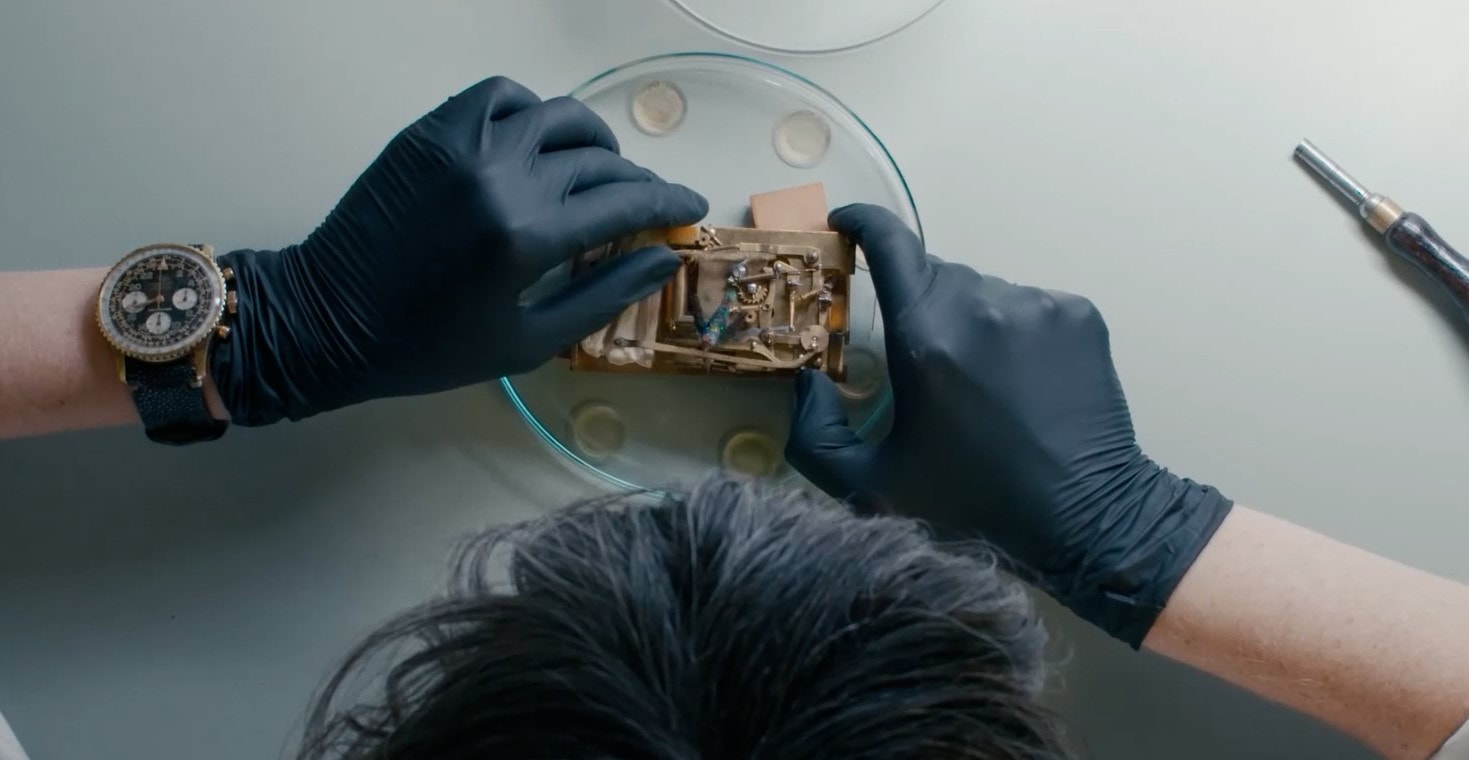

A still from "Making Time" (2023) Time is precious. It’s the one thing that we can’t make more of, no matter how many regretful pleas or wistful wishes. But we can harness time by how we use it. The way we spend our days is one of the truest reflections of who we are and what we’ve been through. For the subjects of “Making Time,” directed by Liz Unna, time is the ultimate measure of human beings. The documentary follows five horologists who design and create exquisite watches using ancient and modern practices. Each subject has a unique perspective on how they got into the world of watchmaking; whether through a personal epiphany, grief after losing a loved one, or a lifelong interest in the craftsmanship. Their experiences help indicate their designs, from imaginative and modern to antique. Told through glimpses of their life stories, the film presents the beauty and the philosophy that watches carry for them.

While the role of horology plays an intriguing part in many people’s lives, Unna barely scratches the surface of what makes her subjects tick. The film moves at a glacial pace and yet feels rushed in its exploration of otherwise prominent themes. Erratic editing disrupts you from forming strong connections to the horologists beyond their philosophical statements. Frequent dramatizations, sentimental music, and cutaways to tiny gears often evoke the feeling of watching one long commercial. Contrary to its title, the documentary makes little time for delving into the subjects’ interior lives enough to make a lasting impression. “Making Time” features the timepieces of watchmaker Ludovic Ballouard, independent watch brand founder Max Busser, antique horologist Nico Cox, hand-made watchmaker Philippe Dufour, and watch designer/actor Aldis Hodge (known for his screen roles including 2020’s “One Night in Miami…” and 2022’s “Black Adam”). The film spends a shaky amount of time with each person, without establishing a strong enough foundation to return to. After each encounter with the subjects and in listening to their perspectives, you are left wanting more insight into why they are so fascinated by and drawn to the world of watchmaking. While admirable in not over-using the “floating heads” approach, which so typically characterizes how documentaries are structured, the non-linear direction undercuts the intrigue of the subjects. The film presents their stories often through narration, rather than spending more intimate time with them directly. By jumping from one limiting presence to another, a plethora of interesting ideas and topics of discussion get lost. We are all constantly in motion. Even on days spent doing nothing at all, time passes us by. One of the more intriguing ideas “Making Time” presents is that each subject themselves is a measure of time. The film becomes a question of how the subjects’ life choices — driven by everything from fear and regret to joy and love — is connected to their work. Through timekeeping, they can’t help but engage in all the formative moments of their lives and how they have spent their time thus far. One subject, Max Busser, recalls his strained relationship with his late father, and the regret of them not having shared strong communication skills. The pain of that regret has led Busser to completely reframe his way of living and follow the pursuits that bring him greater inner joy. The nature of this material prompts you to confront your own place in life, as well as all the dreams you may have abandoned out of fear, social conformity, and more realistically a lack of resources. The art and science of measuring time is fascinating on its own accord. From hourglasses and clock towers, to timers and wristwatches, timekeeping has taken on various forms of precision that point to different ways of life. Some horologists have maintained antique handcrafted practices, while others are engaged in modernized instruments. Each are united by making something with the purpose of outlasting them. You could look at a watch and recognize not only all the time that has passed, but the future of how we measure time. The subjects of “Making Time” evoke various threads of conversation in retrospect, but the film falls short in maximizing their perspectives on both a narrative and visual level. The lack of focus in direction leads to an underwhelming final scene with parting words that feel out of place. While “Making Time” is full of potential, the approach is too concentrated on how the documentary will come across and lets the subjects dictate the direction to the point of repetitively stated self-philosophies. |

Archives

June 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed