|

Kristen Bell in The Woman in the House Across the Street from the Girl in the Window (2022) The line between sincerity and satire is very thin in the adeptly titled Netflix limited series, The Woman in the House Across the Street from the Girl in the Window. Starring and executive-produced by Kristen Bell, The Woman in the House (for short) is a smattering of psychological thrillers that center on “the hysterical woman,” one whose eye witness accounts of crimes are chalked up to “just imagining things”. Series creators Rachel Ramras, Hugh Davidson and Larry Dorf stretch this plot device to eight thirty-minute episodes, each throwing a wrench in expectations. So much is at play in the story, filled with subplots as extra as the series title. In a pile of twists and turns thrown at the viewer, The Woman in the House finds what works and delivers it on a tightrope. At first, it’s a mystery whether the story will fully lean into its satirical slant, if it will surrender to absurdity or carve something more ingenuous from the chaos. The series pokes fun at all the tropes and cliches to be found in its derivative material. The creators also find interesting points to chew on that speak to the addictive quality of psychological murder-mystery stories, and what keeps the viewer hungry in anticipation for a new reveal. The earlier episodes stumble most from standing out amongst the very stories they satirical aim at. Once the screenplay finds its groove, though not particularly memorable in afterthought, it’s easy to fall down the binge-worthy rabbit hole of The Woman in the House. Every night, Anna (Kristen Bell) fills up her glass with wine and cozies up on her sofa by the window, watching the lives of others while hers stays the same. Anna suffers from Ombrophobia, a fear of rain originating from a personal tragedy involving rain. The extreme anxiety attacks keep her inside most nights as a precaution in case skies turn grey. But when neighbor Neil (Tom Riley) and his daughter Emma (Samsara Leela Yett) move in across the street, possibilities light up for Anna. Perhaps a fresh start, a new relationship…a picturesque family to fill the void following a traumatic experience. Stepping outside becomes a little easier. A future seems within reach, until one night she witnesses a murder. Or did she? The age-old question in countless psychological thrillers, ones that portray women’s experiences as hallucinations, that everything they see is actually all in their head and not a serious threat in real life. Most recently, Joe Wright’s adaptation of The Woman in the Window epitomizes the “hysterical woman” not to be trusted, using its protagonist’s mental illness as a means of discrediting her experiences. This is just one of many familiar threads The Woman in the House touches upon, in a way that combines satire with straightforwardness. There’s a wink and a nudge to cliche, and beneath that, a trusting quality towards the protagonist. After Anna witnesses a murder and tells people what she saw, the responses are excessively and expectedly skeptical. Anna’s point of view is deliberately shrouded in hallucination and making the viewer question what is real. But with each episode, the series further stresses there’s a nugget of truth to her perspective. At first it’s not clear which direction the creators want to take. Will the creators fully lean into the satirical slant? Are they trying to find something fresh from a mishmash of repetitive psychological mystery plot devices? The Woman in the House is a bit of both, and while it takes some time to find a happy medium, the absurdity of it all along with an ensemble of game actors make the experience entertaining. Kristen Bell is an actress whose work is mostly unfamiliar to me, hit television shows Veronica Mars and The Good Place being the biggest blind spots. Bell finds plenty to have fun with as Anna, walking that tightrope of playing satire with utmost sincerity. Once a thriving painter, now finds herself drowning in wine and watching life pass her by, reading books like ‘The Woman on the Cruise’. The character lives vicariously through others, with a yearning underneath to somehow return to what her life once was. Bell perfects that duality and gives a performance well suited to the repetitive material. The dialogue moves amusingly in circles, with some vague inspirational quotes thrown in, saying a lot of words without actually saying anything. Bell and a strong supporting cast know exactly what they’re in and deliver fun performances, flipping multiple sides to their characters and adding intrigue to the story. Each episode uses subplots as building blocks, finding so many variations of similar material as the title clearly references. Yet there is still something about this psychological mystery storytelling that makes it easy for the viewer to feel invested and stay for the reveals, of which the series has plenty. Being glued to the screen, for answers to a story soaked in silliness, speaks to its binge-power. Is there much to ponder and chew on when it’s all over? Not quite, but the creators earn their chuckles along the way, indulging in the twists and concluding with their juiciest reveal. The creators have the last laugh with The Woman in the House Across the Street from the Girl in the Window. Keeping the viewer guessing and present in the moment, it’s a series best to binge and enjoy the ride, with a glass of wine or two. All episodes of The Woman in the House Across the Street from the Girl in the Window arrive January 28 on Netflix.

0 Comments

Thekla Reuten in Marionette (2022) One of the ill-fated characters in Elbert van Strien's film Marionette explains that his purpose in this story is to stop the protagonist from thinking. “Don’t think; that’s where all the troubles begin.” Unfortunately this sentiment seems to have overextended to the filmmakers. For the way Marionette unfolds skirts on the surface of its premise and doesn’t delve deep enough to make a resonating impact on the viewer. Marionette tells the story of therapist Dr. Marianne Winter (Thekla Reuten), whose world falls apart when ten-year-old Manny (Elijah Wolf) claims he can control her future. Marianne’s beginnings are somewhat promising; the film introduces her on the move to Scotland. In an attempt to leave behind the residue of a traumatic event, she’s hopeful for a fresh start in life. However, another nightmare is waiting for her in Scotland, as the grey skies and moody atmosphere amplify. Marianne attempts to settle in her new job, the replacement for a children’s psychologist, and meets a troubled child whose drawings hold a strange power. Marionette ponders on the threads of discussing fate vs. free will. Who is pulling the strings of one’s life? How much power does one individual really have to change their own trajectory? Despite how open-ended such questions are, the film leaves nothing to the imagination, instead indulging in one ‘psychological thriller’ cliche after another.

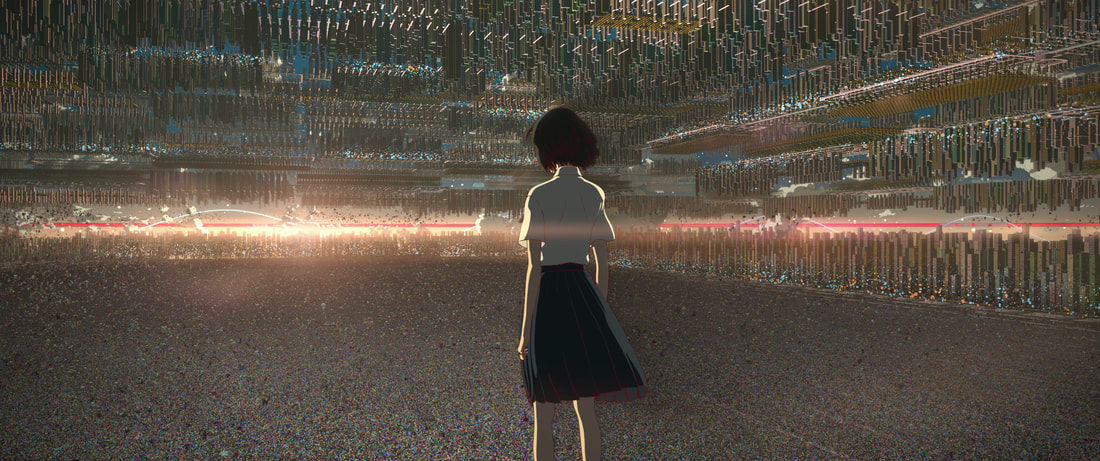

However intriguing a concept is in theory, put into action without focus is another story. Marionette feels directionless; it’s a mystery to solve what van Strien is wanting to say, beyond blatantly pointing out the ‘marionette’ concept at any opportunity. Not much time is given for the viewer to feel connected to the protagonist, and get to know more about her. Marianne is very much in service to a lackluster plot. For a little while, the film begins with the promise of slowly introducing characters as pieces of a puzzle, each one potentially revealing more about what situation Marianne has gotten herself into in Scotland. But the promise for something intriguing quickly dissipates. The film is shrouded in mystery; not in the way that invites curiosity and encourages wonder, but at a level that’s puzzling and frustrating to surrender disbelief to. Marianne is encouraged to entertain a fresh start; with a new job, a potential new companion, a new setting, the story sets up a whole other universe for her. Though much gloomier than the warm and fuzzy flashbacks she occasionally has of a past life. In Marianne’s new life, she is encouraged by colleagues not to go digging or ask questions, despite one child in particular exhibiting some disturbing behavior. The child is attracted to disasters like a magnet. His pictures each represent a horrific event that becomes real when he finishes drawing them. Like marionettes controlling puppets, these drawings seal fate on paper. The concept tries to create a narrative from the cliché often seen in horror movies of children drawing scary, alarming pictures meant to alert their guardians that something is wrong. But the film operates from a level of presuming the story is far cleverer than it is. Marionette moves ten steps ahead of the story, and tacks on unnecessary narration from the protagonist spelling out what’s going on, which takes away greatly from the mystery of how the film will unfold. Muddled dialogue does the actors no favors; decent as most of them are, any sense of mystique is weighed down by an over explanatory screenplay. Unfortunately what’s left is an underwhelming piece of storytelling that buckles under the over reliance of its ‘marionette’ concept. Rather than see the story through with a coherent plot, van Strien spells out every twist and turn along the way. Ultimately taking the wind from its sails and leaving little to no room for the stakes to feel real. Marionette is now available to watch on VOD. A still from Belle (2022), courtesy of GKIDS The gorgeously animated Belle explores the consuming experience of not just having digital platforms as a part of life, but living life inside of one. Writer-director Mamoru Hosoda unveils U, an empowering virtual reality in which people become avatars and vie for popularity among millions. U is a place where anything is possible and anyone can become who they want to be, or at least, who they want to present to the rest of the world. For 17-year-old Suzu, the film’s protagonist, U is an alternate reality away from personal grief and loss. In a remarkable marriage of reality and virtual reality, the story draws out the beauty of making meaningful connections from a digital world. With hints of inspiration from Beauty and the Beast, the film feels like a cyber fairytale. The stunning animation, contrasting virtual reality with the serenity of nature’s landscapes, adds remarkable dimension to the dueling worlds at play in Belle. The story follows high school student Suzu (Kaho Nakamura); she lives in a rural village as a shell of her former self, following a tragic event years earlier. But when Suzu joins the massive online world U, she becomes her persona Belle, a singing sensation who takes the platform by storm overnight. Belle is a transformative figure for Suzu; for one, Belle’s image encompasses an epitome of “standard” beauty and further reinforces a perfected, idealized version of self. From Suzu’s perspective, Belle mirrors the prettiest girl in her class, and amasses fans greatly outnumbering her own friends. As well, Belle’s voice in the virtual world draws from Suzu’s hidden talent in real life. U is where Suzu is able to sing the way she used to, helped by her tech wiz friend Hiroka (Lilas Ikuta) and the instantaneous love coming from millions of viewers. But not all are intent on keeping up appearances and carrying on with the show. One of Belle’s highly anticipated performances is interrupted by an avatar notoriously known as The Dragon (Takeru Satoh). The Dragon is chased out of the performing arena by vigilantes, who’ve been trying to unmask the avatar and consequentially reveal the person behind the screen to keep order in U. The Dragon and Belle cross orbits in the chase, inspiring Suzu in the real world to dig up details about this mysterious avatar and answer the many questions swirling in her mind. The journey leads to an emotional exploration of truth, the reverberating power of being vulnerable and sharing one’s self in a world full of anonymity. Mamoru Hosoda does a wonderful job conveying the double edged sword of anonymity in the digital age. How it gives rise to cruelty without consequence, how it offers escapism for those searching for another life to exist in. On a more positive note, how it sees strangers band together to carry acts of justice, rallying around those in need of support. The film has a strong balance between all the mixed emotions from being a product of this digital world, and trying to find sources of real intimacy from behind the virtual facades that people put up. Hosada strikes a fine line between emphasizing a fantasy world and getting lost in it. With a refreshing perspective, he is actually pushing the story closer and closer to truth. The more this film unfolds, the less artificial it becomes. Stills from Belle (2022), courtesy of GKIDS At its core Belle is a story of compassion and selflessness in the face of struggle. It’s clear with every direction, and all roads lead to the film’s protagonist. Her traumatic past is the bridge between real life and fantasy. Belle merges not just virtual reality and real life, but also Suzu’s past and present. Her most cherished, and most painful memories, along with her hopes for the future. It’s interesting to learn more about her character through the good and bad of the online world, and through her developing a relationship with The Dragon whose identity she grows more protective of. The journey of these characters is an empowering one, about finding your voice and standing in your own truth. Suzu is able to unlock the power she holds within, and work through her grief by sharing a vulnerable part of herself. And when this moment comes in the story, it’s truly one of the most beautifully crafted scenes on film, animated or otherwise. The teensy bit of inspiration Belle lifts from Beauty and the Beast is enough to evoke familiar imagery, but not enough where it becomes a rehashing, or overtakes the central focus of the story. Hosoda engages with many trains of thought and never resorts to the classic fairytale as a fallback. Instead, his search for something authentic and truthful in the shimmering, pixelated world of U carries this film down the road of goodwill and how such a thing may be amplified in a digital age to reach those in need from afar. Belle is a dazzling achievement with as much heart as finesse for the craft of animation. The trajectory of this story packs an emotional punch to the gut, reminding the power of human emotion in a world of ever-increasing technological advances designed to chip away at what makes us human in the first place. |

Archives

June 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed