|

By Nadia Dalimonte Chadwick Boseman, Colman Domingo, Viola Davis, Michael Potts, and Glynn Turman in Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom (2020) Creative tensions are rising at Hot Rhythm Recordings. This recording studio in 1920s Chicago is where the majority of Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom takes place. The film is directed by George C. Wolfe, written by Ruben Santiago-Hudson, and based on August Wilson’s Pulitzer Prize winning play of the same name. Wilson wrote his 1984 play after listening to Ma Rainey, known as Mother of the Blues, sing the titular song. Wolfe’s adaptation is an engaging portrayal of Black artistry and the economic exploitation of performing in an industry that centers white people (white men in particular). Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom has one of the best film ensembles in recent years and features a career-best performance by Chadwick Boseman, a remarkable talent gone far too soon.

The story begins with a lineup out the door of a show in Barnesville, Georgia. Ma Rainey (Viola Davis) is introduced mid performance. As Ma states later on in the film, what counts most for her is the voice inside, not what people think of her. It’s a great choice to establish this character on stage, focusing on the power of her voice, which Davis embodies so wonderfully. After getting a glimpse of Ma Rainey’s talents, the setting switches to Chicago where the four musicians in her band arrive at a recording studio and wait for her to join them. Irvin (Jeremy Shamos), who helps run the studio and constantly assures his co-worker Sturdyvant (Jonny Coyne) that everything is under control, leads the musicians to rehearse in a basement room until Ma arrives. A great deal of the film takes place in this room, and the dynamics that play out are nothing short of emotionally riveting. The framing and focus on the quartet create an all-encompassing feeling of being in that room, watching the actors from up close on a stage. Accompanying Ma Rainey is the quartet of Levee (Chadwick Boseman), Cutler (Colman Domingo), Toledo (Glynn Turman), and Slow Drag (Michael Potts). As the youngest of the four, Levee is playing trumpet in the group until he can make his own way on his own terms. “I’m my own person,” Levee says. In a room full of veteran musicians who play their piece without showing critique despite all the exploitation, his rage and energetic ambition are on the rise. Levee is such a compelling character to watch; Chadwick Boseman brings an enormous spark to the film in his portrayal of ambition and trauma. In the actor’s last film, he delivers an absolutely magnificent performance showcasing his uniquely compelling talent. Boseman elevates a great film into something even greater with his extraordinary screen presence. He works beautifully with the other actors, especially when his character is in conflict with Domingo and Turman (both also excellent in this film). It’s one of the most riveting performances in some time, another example of how the legacy Boseman left behind in film (among so many more spaces) will live on forever. The dynamics beyond the basement of this recording studio are not as engaging to watch unfold. This has more to do with the pacing and screenplay than the acting, as Viola Davis gives a brilliantly complex performance. Easily one of the most talented actors working today, Davis pours her heart into Ma Rainey and delivers with such fascinating embodiment. It would have been interesting to spend more time with her character on a deeper level; the film feels a bit fragmented when the focus switches to Ma and her relationships, not only with her band and the studio but also with Dussie Mae (Taylour Paige). Davis still opens a window to all of these dynamics and brings an immaculate level of detail to exploring her character. With the limited number of sets and framing, Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom shines as a character-based story with an incredibly talented ensemble. The actors guide the way through stunning monologues and compelling interactions, revealing more about who their characters are as individuals and in relation to the world they are living in. George C. Wolfe does a wonderful job establishing the sets and adapting the stage material in a way that feels invigorating instead of strained. Each of the performances soar in their own way and add many resonating layers to a story that explores ambition and artistic erasure.

0 Comments

By Nadia Dalimonte George Clooney and Caoilinn Springall in The Midnight Sky (2020) The stakes feel incredibly low in The Midnight Sky, a dull post-apocalyptic adventure story starring, produced, and directed by George Clooney. Clooney makes a cosmic return to the screen with a project that looks grand, but stumbles with the source material. Based on the 2016 book ‘Good Morning, Midnight’ by Lily Brooks-Dalton, the film follows scientist Augustine (Clooney) who discovers a young girl named Iris (Caoilinn Springall) left behind on his isolated observatory in the year 2049. As the two form an odd bond and find themselves weathering Arctic storms, a parallel thread follows a group of astronauts aboard the spacecraft Aether, headed home from a planet they hoped would be the future. But waiting for them on Earth is an ecological catastrophe threatening the livelihood of all inhabitants. Augustine tirelessly tries a poor radio connection to warn the Aether crew of the dangers ahead.

Lily Brooks-Dalton’s book has an intriguing premise dipped in loneliness and ambition. The story looks at the world’s end through the perspective of characters who are isolated, as their ambitions carry them to a life detached from Earth. Augustine is a celebrated astronomer who has given most of his life to observing the origins of the universe from remote outposts. The beginning of the film introduces him at his current posting, a snowy Barbeau Observatory in the Arctic Circle, of which he’s a terminal patient. Upon the news of a global catastrophe, while the other scientists evacuate, he stays behind in declining health and unrelenting dedication to his work. It’s an incessant ambition Augustine is evidently used to; in hazy flashback scenes of his younger self (Ethan Peck), his partner Jean (Sophie Rundle) urges that he take control of his life otherwise he will lose human connection. There are pangs of regret to Clooney’s character that the actor plays well; he doesn’t have to say much to get the feeling across, as his somber portrayal of Augustine has a lived-in quality to it. The Midnight Sky has potential on the surface, particularly as a character portrait of loneliness and longing for universal truths through confessions of a lonely mind. But what makes the premise intriguing gets lost in muddled storytelling. Mark L. Smith’s adapted screenplay flickers through plot points without the patience to let them flourish. As a consequence, moments of heightened emotion and moving scenes between the characters fall flat. There are two main threads to this film, and the parallels are drawn poorly from inception all the way to a puzzling ending. Augustine and Iris have a mostly quiet relationship; her appearance in the film is a sudden revelation for him. A reminder of someone he loves dearly. The two eventually find a way of communicating that works. As they brace the blistering elements to find another radio connection, a parallel story follows the group of astronauts aboard the isolated Aether traveling back home. The Aether crew is played by a star-studded cast including Felicity Jones, David Oyelowo, Kyle Chandler, Tiffany Boone, and Demián Bichir. With this much talent in one setting, it is especially disappointing that the screenplay (mainly the character development) are what bring the film down several notches. Each have good little standout moments throughout, but the lack of focus in storytelling trickles down to their performances as they try to elevate above an incoherent screenplay. Moments of emotional engagement feel few and far between in The Midnight Sky. Clooney’s direction is fine; there are some lovely celestial scenes that reflect and compliment Augustine’s frame of mind in particular. He establishes a strong setting of isolation in the Arctic; interrupting the quiet atmosphere are some messy action sequences that appear on screen in mostly jarring ways, and feel strategically placed simply to incorporate tension. Alexandre Desplat, who usually delivers, adds a super sentimental soundtrack to the story. There are also some jumpy musical notes that often don’t gel with certain moments. From a technical standpoint, the film is hit or miss throughout. For every moment of spectacle, there is one of distracting visual effects. At the heart of The Midnight Sky is a group of isolated individuals trying to find their way home. There is potential for an emotional impact here but it never reaches the surface. Clooney brings ambition to the film by drawing parallels between the two storylines. By the end of its 2 hour runtime, however, it becomes clear that not enough patience was implemented along the way for all the threads to truly come together in a coherent or engaging way. Note: this is my second review for Nomadland. Read the first here! Frances McDormand in Nomadland (2020) Played so seamlessly by Frances McDormand it’s a wonder where she begins and her character ends, Fern is a nomad deep inside. She has a real sense of belonging on the road, where home is not a structure but a feeling. Beautiful landscapes are her museum, and she is the voluntary tour guide. McDormand works her magic in collaboration with the phenomenal Chloé Zhao, who edited, co-wrote, produced, and directed Nomadland. Within the first few minutes of the film, a powerful story is told. Due to reduced demand for sheetrock, US Gypsum shut down its plant in Empire, Nevada. The shuttered town and its discontinued zip code pushed all residents to relocate. One of the residents sifting through the debris of a once thriving life is Fern. In our introduction to her journey, she holds onto her husband Bo’s jacket extra tight before bidding farewell to some belongings and starting up her trusty van. Full of personal trinkets and treasures, she built the self-named Vanguard from the inside out. Her van is her home, and has been for some time. In the aftermath of personal grief and loss, Fern is on the road in search of answers.

Chloé Zhao’s curiosity as a director is the perfect match for this story. She brings immaculate detail to the narrative and also maintains a beautiful openness in her approach. She collects human interactions like rare gems; each nomad encounter is given empathy and space for expression. Zhao introduces many of these characters in the first act of the film, as they gather around a campfire and share stories of what led them to this lifestyle. What they share in common is a gravitation towards nomad Bob Wells and his cheap RV living guide. Although brief in screen time, he takes on a nucleus role in the film as Fern (among others) visits him to share her experience in search of some guidance. As vast as all the landscapes are, it’s a small world and the people in it gravitate towards a shared connection. As Bob tells Fern in a moving scene, months or even years could pass by and he’d see the same people down the road again. The screenplay was adapted by Zhao from Jessica Bruder’s non-fiction book, ’Nomadland: Surviving America in the Twenty-First Century’. The book is about American nomads, many of whom were affected by the Great Recession, who embark on the road in search of work and a new way of life. Most of the locations and people in the book made it onto the screen; staying close to Bruder’s perspective gives the film a brilliant level of world building. Zhao starts with establishing location and creates the characters from there. Real nomads come to life on screen through monologues and small everyday interactions that reveal a bit about who they are. Two nomads in particular - Linda May and Swankie - are given revealing moments where they explain why they’re on the road. Listening to their stories is like hearing their souls speak. These moments are beyond moving to watch, and are the perfect example of why the film strikes a resonating chord in my heart. Zhao’s screenplay feels incredibly intuitive and personal in telling a story about this particular nomadic lifestyle. She brings so much heart to this film, and sits patiently with the people in this world to hear their stories. To quote Chloé Zhao, “there are not many people out there as strong as Frances McDormand looking you in the eyes.” In creating the character of Fern, who might be McDormand’s alter ego, Zhao needed someone who would fit in the environment. She needed a good listener…someone who would absorb her surroundings, go with the flow, and also be deeply invested in the people she comes across. Frances McDormand’s screen presence is one of the strongest in film history, and her familiarity works to the film’s benefit as Fern becomes a guide for the audience to explore this nomadic world with. Whether it be working at Amazon, polishing rocks, or running a badlands spa, McDormand lends herself fully to the role. There are some playful moments in the film where the actor and character mesh. “Try McD,” suggests Fern when a receptionist can’t find her name on a camper registration list. McDormand’s performance is a magnificent blend of nuances, powerful stoicism, and surprises. The character of Fern, like many others passing through in Nomadland, lost the life she knew after the Great Recession. She and her husband had lived in Empire for many years. Empire was a town Bo loved and that loved him back, so she stayed behind because “what’s remembered lives”. The film resonates as a story of grief and finding ways to cope with loss. Fern’s search brings her to a nomadic lifestyle where her self-sufficiency is tested, but there is also an excitement in seeing what’s down the road for her. She finds a special friend in Dave (the great David Strathairn), a familiar face she runs into at various camper locations. Their dynamic is so pure and genuinely lovely to watch unfold. Similar to Fern, Dave takes the odd job here and there to keep afloat. When Fern meets up with friend Linda May in the badlands, there Dave is, working as a guide for tourists. Dave and Fern share some of the most stunning scenes in the film, from wandering off into enormous rocky terrain to gazing at the stars. In tune with Zhao’s direction, Joshua James Richards’ cinematography gives the film a beautiful cinematic lens while also maintaining the openness of their natural environments. The feeling of being in nature can be humbling and relaxing, followed by a restlessness that rushes in when you leave such a setting. The film captures this emotion so brilliantly, and it’s infused in Fern, who finds comfort in being on the road but shifts restlessly under a roof. Chloé Zhao and Frances McDormand are a match made in heaven as they explore the healing power of nature in gorgeous American landscapes. The beautiful score by Ludovico Einaudi gives melodic reminders that underneath the protagonist’s stoic exterior is a search of life after loss among a community of grieving people. Nomadland is a stunning character study and a moving portrait of learning to live with grief. Zhao tells a timeless story about self-sufficiency, unshared emotions, and the lonely ache in finding a sense of belonging during times of isolation. By Nadia Dalimonte Tessa Thompson in Sylvie's Love (2020) Writer-director Eugene Ashe stimulates love at first sight in Sylvie’s Love, a gorgeous sweeping romance that exudes charm in every frame. An incredibly talented cast, featuring Tessa Thompson and Nnamdi Asomugha in the two lead roles, soar at bringing a heartfelt narrative onto the screen with compelling fluency. Lush costumes and detailed cinematography, paired with dreamy music, depict a glamorous 50s/60s setting in Harlem. With passion, a rekindled love story is told through changing times and newfound professional heights.

The story begins with a chance meeting outside a theater. As Sylvie (Tessa Thompson) searches for a no-show guest, a familiar face passes by. Emotions rush in as her eyes meet Robert’s (Nnamdi Asomugha). The history they share sizzles back in time to one hot summer day five years earlier. Robert, an aspiring saxophonist playing for a jazz quartet, notices Sylvie through the window of her father’s record store. Aspirations of becoming a TV producer linger in her thoughts as she spends the summer indoors, waiting for her fiancé to return home. Her eyes are glued to the television as her future love walks through the door holding a Help Wanted sign. As the two slowly bond through music, her father takes notice and hires him on the spot. With the bloom of an unexpected romance, Sylvie finds herself at a crossroads between her fiancé and a new love that sparks fluttering emotions. Then life happens; Robert gets an exciting opportunity in Paris, and their paths diverge. But their spark never wavers as the years go by. Eugene Ashe beautifully establishes the blossoming connection between both characters, while also exploring Sylvie’s hesitations about her overwhelming feelings for Robert. They fall deeply into each other’s hearts…perhaps too soon, as the ‘Fools Fall In Love’ melody goes. Tessa Thompson and Nnamdi Asomugha share such winning chemistry full of longing, meaningful moments left unshared, and the underlying fear of losing each other. Thompson plays a more fleshed out character, particularly in the second half of the film which sees a rise in Sylvie’s producing career and explores the aftermath of success in her family household. When her path crosses Robert’s again, harking back to the opening scene, their chance meeting takes on a whole new intriguing life. Just as Sylvie retreats from Robert when his career takes off in the first half of the film, he feels a similar urge not to hold her back when she achieves success in the second half. Tessa Thompson has fantastic versatility. Her stunning work in films such as Little Woods, Creed, and Sorry to Bother You is now joined by another wonderful performance in Sylvie’s Love. Her screen presence is absolutely magnetic from start to finish, spanning a complex whirlwind of emotions as Sylvie’s devotions to her personal and career ambitions continue to rise. The film plays out as a grand love story at its core, but there are also interesting portrayals about the rollercoaster of pursuing career aspirations and how this clashes with expectations of creating a family. Sylvie’s fiancé Lacy (Alano Miller) in particular gets caught up in loving his antiquated idea of her. The second half of the film also sees strong dynamics within the television production industry. Sylvie lands the job of assistant to Kate (Ryan Michelle Bathe), the head producer of a 60s cooking show that stars TV personality Lucy (Wendi McLendon-Covey). During the job interview, much to Sylvie’s pleasant surprise, she discovers Kate is in fact the producer. It’s both a wonderful and sad scene touching on long overdue necessary industry shifts. Sylvie's Love is a gorgeous romance that resonates beyond the blossoming love story at its core. The film is full of so much joy, which is also essential for Black representation on screen. The narrative portrays interesting explorations of career ambitions, self-love, and different relationship dynamics. Sylvie’s closest friend Mona (Aja Naomi King) has a small but recurring role throughout the story, and adds to a strong portrayal of friendship. Ashe’s direction and writing also infuse a passion for music that shines through the characters. Robert in particular is holding onto his love for jazz as its popularity starts to change from the late 50s to the 60s. An exquisite soundtrack gives so much emotional weight to certain scenes and the songs that accompany them. Musically, visually, and story-wise, this is a beautiful film. Eugene Ashe does a wonderful job of balancing all these elements together and bringing focus onto many of Sylvie’s loves in this story. By Nadia Dalimonte Ariana DeBose and Jo Ellen Pellman in The Prom (2020) Ryan Murphy’s The Prom, adapted from the Broadway musical of the same name, is full of energy and has a heartfelt story. Sporadically endearing and fun moments show promise for what could have been the case as a whole. The gorgeous set design, glittery costumes, and some lovely performances from an all-star cast (Meryl Streep and Keegan-Michael Key especially) shine bright. Newcomer Jo Ellen Pellman and co-star Ariana DeBose are so charming to watch. At the core of this narrative, there are great essential messages of acceptance and finding your light. But the end result of The Prom doesn’t sparkle enough to maintain its lengthy runtime. Mostly forgettable musical numbers and an unfortunate casting decision distract from the resonating heart of the story.

The story follows a group of former Broadway stars who have lost their glitter, putting them in a professional rut. After receiving particularly harsh feedback from an Eleanor Roosevelt-inspired show that flops, Dee Dee Allen (Meryl Streep) and Barry Glickman (James Corden) wallow in defeat. They confide in fellow former stars around them, namely chorus girl Angie Dickinson (Nicole Kidman) and child actor/bartender Trent Oliver (Andrew Rannells). The glitter is fading; entering crisis mode, they desperately crave good PR that will wash them clean and get them back into good graces with the public again. Angie, wistful for Chicago’s leading role of Roxie Hart, suggests they need a cause to support. But their celebrity activism doesn’t go according to plan. The film opens with PTA head Mrs. Greene (Kerry Washington) leading a ban on gay couples attending a high school prom in Indiana. News reaches the stars, and after a few Twitter scrolls, they find a headline about a high school girl named Emma (Jo Ellen Pellman) whose prom gets cancelled because she wants to take her girlfriend Alyssa (Ariana DeBose) as her date. Desperate to boost their public image and save the day, the starry troupe show up at the Indiana high school in support of Emma. Unbeknownst to them, Emma needs to tell her story in her own time, in her own way. Emma doesn’t wish to be a scapegoat, or a martyr, or a cautionary tale. She just wants to dance with her girlfriend at prom. Jo Ellen Pellman is a shining star; she’s a joy to watch and gives a resonating performance. She also shares delightful chemistry with Ariana DeBose, whose character is feeling the pressure and not ready to come out to her mother. It would have been great to see both characters explored in even greater detail as individuals and as a couple. Instead a lot of the focus is pulled back towards character arcs of the self-obsessed theater troupe, which has its pros and cons. The troupe’s Indiana visit proves to be much more personal than they anticipated. Broadway star Dee Dee’s self-centered personality is challenged when she meets high school principal Tom Hawkins (Keegan-Michael Key), a passionate theatergoer enamored with her work. Dee Dee’s performances are an escape that help Tom heal. His pure love and admiration for her stage persona is put to the test the more they get to know each other. Their bond is incredibly endearing to watch unfold, in large part thanks to great performances by Meryl Streep and Keegan-Michael Key. They have lovely chemistry and the film soars up a notch whenever they appear on screen. In addition to sharing a charming bond with Key, Streep brings expected pathos and has fun with her musical numbers, particularly a great solo early on. Key also has a great number that speaks to the healing power of entertainment and particularly theater. The rest of the cast are mostly fun but a bit wasted, particularly Nicole Kidman who shines brilliantly in every single brief moment but doesn’t have much to do apart from a fun little zazz number with Pellman’s character. It’s one of the few memorable numbers in the film. Andrew Rannells and Kerry Washington are good with the material given. The most unfortunate piece of acting comes from James Corden, who evidently tries hard but misses. Considering his character’s emotional journey and increasing screen time, his miscast performance takes center stage and brings down the energy of an otherwise fine film that works to celebrate an essential message. By Nadia Dalimonte Rachel Brosnahan in I'm Your Woman (2020) Julia Hart’s hypnotic new film, I’m Your Woman, brings a compelling character study to life in the 1970s world of crime. With an intriguing perspective and precise attention to detail, Hart explores themes of regaining identity and discovering newfound motherhood. The stylish opening sequence and simple recurring piano score lend sophisticated qualities to a story that stirs in moments of eerie stillness. Hart, who co-wrote and directed the film, gives each frame a beautifully controlled level of patience and care. I’m Your Woman adds a refreshing point of view to the crime boss genre and pairs Julia Hart’s directorial skill with a marvelous Rachel Brosnahan to craft a satisfying slow-burner.

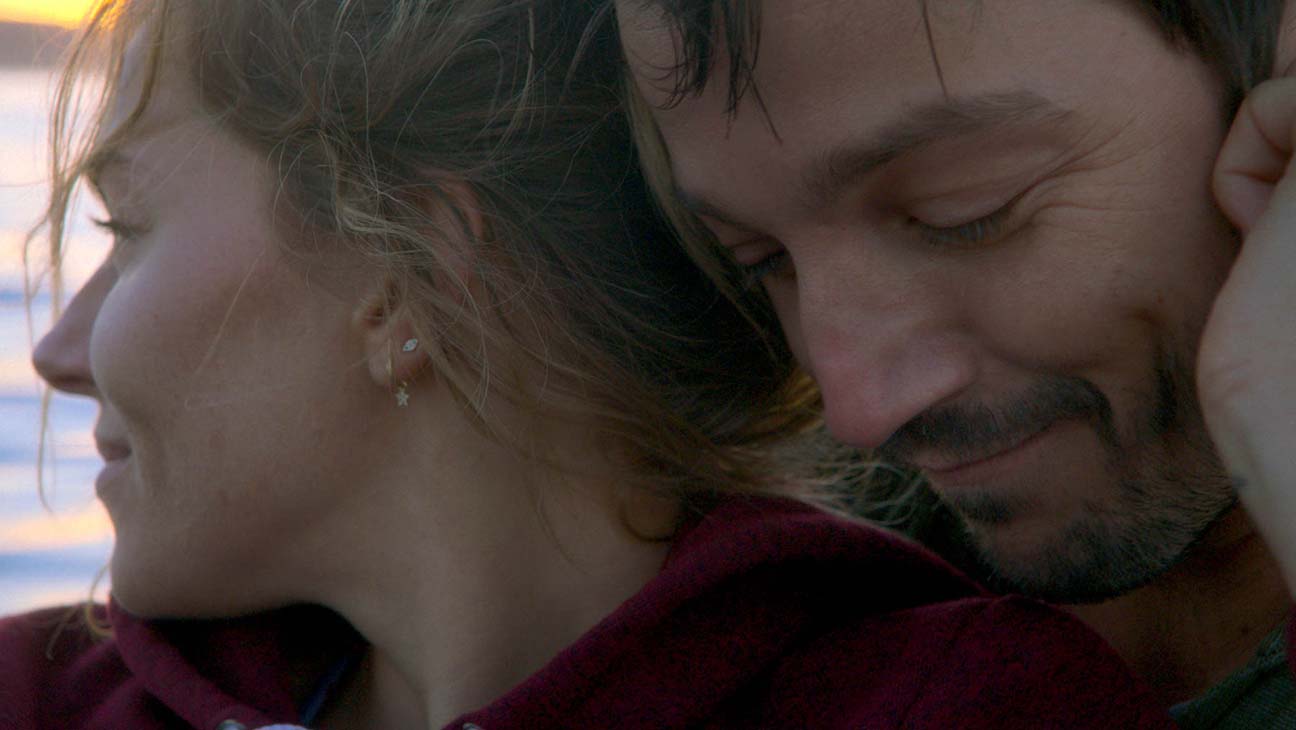

The phone rings a lot in Eddie and Jean’s house. Off the hook, in fact. A smart little detail hints at the increasingly prying activity surrounding this household. We later learn Eddie (Bill Heck) lives a life of crime, but in his introduction, he’s a mysterious character who comes home one day holding a baby for Jean (Rachel Brosnahan). Without explanation, she now has a baby in her life, and she goes with it. To make matters more mysterious, one night Eddie doesn’t return home. Banging on the door startles Jean out of bed and ultimately, out of the life she knows. Handed big bags of cash and met with a man named Cal (Arinzé Kene), she’s suddenly starting over with a baby. Everyone’s looking for Eddie, and they’re looking for her too. Hart makes the refreshingly great choice not to delve into detail about who Eddie is, what he did, and why everyone is in danger. Instead, she stays with Jean every step of the way as the character is given a new home and is kept in the dark. The narrative focus on Jean gives the film an encompassing feeling that you’re on the journey with her, moving every inch with purpose and waiting every minute in stillness. In her newfound moments of quiet, she’s also coming to terms with newfound motherhood, and her instincts are swift. The film moves slowly and surely with impeccable tension. The pacing evokes a constant fear that Jean will be found out at any given moment. Warned by Cal not to let anyone in (literally and figuratively), she lives in the shadows of ‘temporary home number one’ on a sleepy street, comforting her baby’s continuous cries through the night. It is at this home where the outside danger manifests in very different ways, starting with a seemingly well-meaning neighbour named Evelyn (Marceline Hugot), wanting to know who moved into her friends’ old place. The chill from seeing her calm, eager face appear at Jean’s front door in the dead of night is palpable, and her candygram visit takes an eerie turn when she asks where the restroom is. The direction and editing are particularly great in establishing moments of tense uncertainty. All of Jean’s suspicions are projected onto her surroundings, which creates an engaging experience of watching her encounters and keeping a closer eye on her settings. As the film slow builds to ‘temporary home number two’ in the woods, the screenplay shines more light on Jean beyond the situation she’s in. Hart, who co-wrote the film with Jordan Horowitz, crafts an intriguing exploration of a character on a journey of self-discovery. The more Jean learns about Eddie and what could come next, the more empowered she feels to take matters into her own hands. Contrary to the title, she is not anyone’s woman but her own, and she proceeds to regain her sense of self. An unexpected visit from an unknown family of three at her new cabin presents some startling truths that prompt her to practice self-defense. The introduction of this family (Teri, Paul, and Art) raises the stakes up another level and gives a glimpse into the mess of a city they all left behind. Teri (Marsha Stephanie Blake) in particular is an enormous highlight to the story. Her character adds a resonating layer that strikes a chord with Jean personally. With a newfound bond, the two pair up to take matters into their own hands when they sense something is wrong back in the city, where the story startlingly quickens the pace. I’m Your Woman excels as a quietly gripping slow-burner with great performances, beautiful cinematography, and a pitch perfect 70s soundtrack. An emotionally gratifying conclusion recalls a great monologue from Rachel Brosnahan halfway through the film. She tells Cal how she burned all her personal desires until there was nothing left but the fire, and then Eddie walked in with a baby. What she stopped wanting was suddenly in front of her, and their linked journey is a big part of the film’s core which makes its conclusion an incredibly resonating one. By Nadia Dalimonte Sienna Miller and Diego Luna in Wander Darkly (2020) Wander Darkly is a disorienting rollercoaster of emotions that slips through time to explore interpretations of the truth in a couple’s relationship. Adrienne (Sienna Miller) and Matteo (Diego Luna) are getting through their first year as new parents. They have a baby girl, a new home, and their lives together seem full of possibility. But are they truly happy as a couple? During a rare date night, Adrienne reflects on her future in the passenger seat. They both deserve to be happy, she insists to Matteo. The two share a tense conversation full of nuances about stability, as Adrienne questions the point of them being together. Amidst the frustrations about their relationship, they are suddenly thrown into the aftermath of a traumatic event.

Adrienne wakes up from an accident in a jarring daze, watching in horror as her supposed death flashes before her eyes. Matteo talks her down a ledge and explains that she’s been in a puzzling trance, but she seems to think that she now exists in the afterlife. The film introduces an intriguing premise, and while there is an over-reliance on this nightmarish concept, the story finds some footing as an exploration of lost love. Writer-director Tara Miele is in search of truths, not just about what’s happening to the protagonist but also about why Adrienne and Matteo fell apart as a couple. At the fragmented heart of Wander Darkly is a love story. The film revisits the couple’s relationship from its shy and intimate blossoming to its emotional development. Echoing vibes of Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, Adrienne and Matteo retrace their memories and jump through time in search of what they lost. What remains a mystery, until the end, is which parts of the story are reality and which emerge out of imagination. At a certain point comes the predictability of where the story is going, and the film loses some of its momentum going into the final act. But there is still plenty of intrigue to be found, particularly in Adrienne’s journey of regaining balance within herself. The film is told from her frame of mind, and her vulnerable adaptation to a completely new way of life is moving to watch. Sienna Miller is wonderful in this role; like a ghost finding purpose, she wanders in search of what happened to her and revisits the past to uncover a level of truthfulness she couldn't see at the time. Her performance is a beautiful portrayal of fragility and frightening uncertainty. Joined by a very charming performance by Diego Luna, the two elevate the material and create a believable portrait of a crumbling relationship that gives weight to the ending. Wander Darkly takes a disorienting approach to a relationship and uses strong technicalities to follow a fragmented mind. The camera movements create some interesting illusions to portray the ups and downs of Adrienne and Matteo’s life together. The editing compliments the story quite well, avoiding a mess of confusion. What resonates most about Tara Miele’s feature is how personal and aspiring her perspective feels. She explores the interpretation of truth in a challenging way, puts an ambitious spin on a love story, and experiments with a concept that doesn’t always work in action but comes from a place of authenticity. By Nadia Dalimonte Christopher Abbott and Aubrey Plaza in Black Bear (2020) Cabin fever meets chaotic mind games in the wildly energetic film Black Bear, written and directed by Lawrence Michael Levine. This film ticks in mysterious ways…it maintains an erratic pulse that adds fuel to the disintegration of relationships. The story of Black Bear, much more puzzling and intricate than how it appears on the page, unravels in an insanely deconstructive way that sees characters in conflicting lights. Guiding the dense experimental nature of the film is a phenomenal performance by Aubrey Plaza. She takes you on a dysfunctional and intoxicating journey of a filmmaker who gathers influence from setting.

Black Bear follows Allison (Plaza), a filmmaker who seeks inspiration at a rural lake house, hoping an isolated setting would solve her writer’s block. But this remote retreat in the woods conjures up everything but peace of mind for her. Allison is a guest in these woods; Gabe (Christopher Abbott) and Blair (Sarah Gadon), the doomed couple who inherited the house, welcome her into their complex little world that Gabe especially manipulates. The film comes to life once the dynamics spark between the trio, particularly through snappy dialogue with a whole lot of subtext and even more shared tension. In the span of an evening, the characters are totally deconstructed as they each get confronted with truths about themselves. Given how quickly the tension rises, along with the heightened personal stakes each character has, one setback could set everything aflame. When we reach the breaking point, the film completely shifts gears and mutates into something else entirely. Levine breaks down these central characters and reveals them in a ‘behind the scenes’ light that is even more engaging than the first part of the film. The story feels very much like a puzzle, with each piece fitting into a bigger picture. What is the bigger picture of Black Bear? At the core, it’s about the making of an independent film in the woods. It’s about nightmarish ideas swirling around in Allison’s head and spilling out…somewhere. Levine leaves behind a lot of questions to chew on in terms of locating the blurred line between reality and imagination. With so much up for interpretation, there’s a lot to unpack and piece together. There’s also a great deal of trust that Levine puts into the audience to fill in the blanks. What keeps the lines blurred is an impressive attention to detail and a seamless transition between two very different halves of one film. The entire energy and physicality of the second half is such a stark contrast to the first. This experimental nature of the film gives the actors an opportunity to flex new muscles, and they each do so brilliantly. Aubrey Plaza is up for the challenge and gives one of the best performances of the year, by far. She fully commits to the reality of each moment, and given the meta aspect of this film, she also traces a subconscious thread (or thought process) within her character that ties her entire performance together. Allison is a character who longs for inner peace; during the second half in particular, her process is disrupted in a toxic environment which takes a devastating toll on her. Through her character, the film also explores the dangers of blending a personal relationship with a professional one. It’s such an intriguing role, like something born out of a fever dream, and Plaza absolutely nails it. With a performance of this magnitude existing at the center, the film maintains a great level of uncertainty for what will happen next. Plaza shares electric chemistry with her co-stars Christopher Abbott and Sarah Gadon, who each fuel the story with their committed turns. Together they tread the waters of yearning for truth while also bearing witness to artistic collaborations at the expense of a disintegrating relationship. One of the themes Black Bear explores exceptionally well is the pitfalls of working with your partner on an artistic level. The relationship between director and muse takes center stage. Levine pulls this dynamic apart, piece by piece, to show an extreme version full of manipulation, neurosis, jealousy, and the mind games born from lust and desire. The artist-muse relationship is just one of many dynamics that Black Bear explores. What makes this film so engaging is how the story branches out in so many interesting directions without feeling totally disjointed on the whole. As insane and as puzzling as all the scenarios are, Black Bear finds a footing by staying close to the chaotic nature of independent filmmaking and going with the flow of each moment. The film ties together really well, which is largely thanks to a commendable performance by Aubrey Plaza gnawing at the heart of this nightmarish fever dream. By Nadia Dalimonte Saoirse Ronan and Kate Winslet in Ammonite (2020) Writer-director Francis Lee cracks open a chilly exterior to find warmth in his latest film Ammonite, a beautifully delicate character drama about a woman who unearths passion through paleontology. The story is set in 1840s England and is loosely based on the real life of Mary Anning, a fossil hunter who was not recognized in her lifetime for the contributions she made to paleontology development. Ammonite follows Mary (Kate Winslet) late in life, when fossils have become unpopular but she still trudges through sand and operates a little shop by the sea. She lives with her mother Molly (Gemma Jones), who has suffered unspeakable loss and is dealing with a relentless illness. The two have a fractious relationship, but they have the best intentions for each other at heart. Mary's shop sees little action until she receives a visit one day from an upper class London couple, Roderick (James McArdle) and his wife Charlotte (Saoirse Ronan). Roderick, who takes interest in fossils, asks Mary if she’ll take Charlotte under her wing and teach her about fossil hunting in the hopes of lifting her out of grief. Having experienced a devastating loss, Charlotte is in a persistent state of melancholia.

The two women meet very early on; it’s not until halfway through the film that their relationship intensifies, which makes room for a crackling slow burn on course to an all-consuming romance. Charlotte is a broken character with great capacity to give love, and her outward display of affection unlocks something in Mary’s steely demeanor. With a glance here and a slight touch there, the characters’ interactions gradually build up to reveal glimmers of repressed emotion. Francis Lee works through the story by exploring with an intent focus on physical interactions. Every movement feels very character based and character driven. The film moves with a gradual melody that is both intimate and hypnotic. Mary and Charlotte slowly discover that they can both give each other the comfort in feeling understood and knowing they are not alone. The pacing of the story takes time and patience to delicately unearth their relationship and bring warmth to a chilly atmosphere. One of the pitfalls of a quiet, slow burn approach is losing the momentum that simmers beneath the surface. But with Lee’s character building, the film seldom loses its passion no matter how tranquil. It’s still there, simmering on, which is also a testament to incredibly detailed performances. The way Mary exhibits such still energy in how she carries herself, both emotionally and physically, is very different to Kate Winslet’s previous work. She often plays characters who wear their heart on their sleeve and energize a room. While it’s not a surprise that she’s brilliant in this film, it’s intriguing at this stage in her long career to watch her play a person so composed and emotionally held. It’s interesting that she doesn’t have a big moment of completely unfolding and pouring her heart out. She comes close (for her at least) at times, but never does. Mary holds everything in, and in the few moments that she does express herself whether through joy or ache, she shows how the character comes to be unlocked by Charlotte. Winslet brings a fantastic level of restraint that sizzles not so much in words, but in glances and body language. The tiniest expressions carry so much weight thanks to the immaculate detail she infuses in one of the greatest performances of her career. The realization of not being understood is one that aches deeply, and there is a point in this film where Mary has this fear during one of her and Charlotte’s most fervent interactions. Yes, Charlotte has an effect on her and unlocks something in her, but Mary still has her guard up. These are two characters who seem contrary in their energy, but they each possess qualities that keep them interconnected in the real world. Complementary to Winslet’s emotional labour is Saoirse Ronan, who infuses an infectiously giving nature into Charlotte. It’s easy to see why their bond doesn’t waver when reality kicks in; Ronan does a lovely job of portraying the interdependency Charlotte shares with Mary, as well as the manifestation of Charlotte’s own search for a loving connection at a most vulnerable time. There’s also a lightness and inviting energy to Ronan’s performance that gives rise to Winslet’s growing comfortability around her. It’s easy to see why Mary feels she can drop the weight of her experiences when spending time with Charlotte. When it’s just the two of them, the rest of the world melts away. There’s something incredibly moving about an emotional door being opened for Mary, as she’s given a moment to be understood. Charlotte unlocks something in her in a way that others could not, as Mary’s ex-lover Elizabeth (Fiona Shaw) muses. With the little screen time Shaw is given to establish her character, she has a wonderfully intriguing impact on the film and makes it quickly evident that the two characters have a history. Shaw and Winslet share a beautiful scene in the final act during which Elizabeth reflects on the pitfalls of their relationship. Mary has an added layer of unfulfilled potential when the film addresses her name being erased from history. Part of the weight that she carries around stems from the fact that she was not properly acknowledged in her lifetime. She spends all this time digging and brushing fossils, an arduous task as Charlotte amusingly explains in one scene when she tells off a prospective buyer who visits Mary’s shop. Mary is deeply involved in her work, and not only is she overlooked, but her achievements are stolen from her. Men take all the credit for her discoveries, replacing her handwritten notes and signature with a standard description card. There’s a quietly moving scene of Mary wandering around a British history museum, seeing her work with somebody else’s name on it. In this moment comes the realization that Ammonite is not just about love between two women. It's also about Mary's unwavering love for her work, and the sense of responsibility she feels to give herself to it. Much like the protagonist, Ammonite has a tough exterior that melts with the potentiality of a warm and loving embrace. The film is a thoughtful and studied look at a particularly emotional moment in Mary Anning’s life. Accompanied by a lovely Dustin O'Halloran & Volker Bertelmann score, gorgeous cinematography and costumes, the story unravels hypnotically with the perfect blend of drama and occasional humour. At the dormant heart of this story is a woman whose yearning to be understood unlocks the door to rediscovery and slow builds to an ending full of hope. Ammonite releases on demand December 4th. |

Archives

June 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed